“The papers of Aristotle had suffered grievously and were in places illegible; but Apellicon occupied himself with copying and editing them. Tyrannion found that the editing of Apellicon was excessively bad. Ultimately, the peripatetic scholiarch Andronicus of Rhodes undertook the arrangement of the papers, the correction of the text, and the publication of the new edition.”

The papers of Charles Peirce may not have not suffered as grievously from damp and insects as those of Aristotle, but their general state of disorganization and partial subjection to arbitrary editing have long required peripatetic editors to undertake their arrangement and their correction in order to publish them in a new edition. Extensive information regarding the methods followed to produce the edition is given under the Methods tab.

As a selective but comprehensive chronological and critical edition, the Writings of Charles S. Peirce covers the full range of Peirce’s published and unpublished texts on any subject in a chronological sequence that reveals his often simultaneous work across many fields of study. Larger sequences of writings are grouped together within a volume if they represent a fairly concentrated period of work. The need for a chronological edition is especially strong in Peirce’s case; earlier editions were either topical or limited to a small selection of works, and provided little sense of his evolving thought or sufficient context for the massive body of his unpublished writings.

The core of the edition consists of several components:

“This new edition of Berkeley’s works is much superior to any of the former ones. It contains some writings not in any of the other editions, and the rest are given with a more carefully edited text. The editor has done his work well. The introductions to the several pieces contain analyses of their contents which will be found of the greatest service to the reader.”

This two-volume chronological edition makes available a comprehensive selection of Peirce’s most seminal philosophical writings. All the texts included are classics that will continue to influence the way philosophers think for centuries to come.

Work on this edition began in 1991 when Nathan Houser and Christian Kloesel agreed to prepare a two-volume collection of Peirce’s philosophical volumes suitable for university seminars. Houser and Kloesel completed Volume 1 in 1992 and made a preliminary selection for Volume 2, but were unable to carry that work through to completion. In January 1997, the Peirce Edition Project agreed to finish the selection and to undertake the editing for Volume 2. It appeared in the spring of 1998. Royalties for both volumes have been assigned to the Peirce Edition Project.

Volume 1 presents twenty-five key texts, chronologically arranged, beginning with Peirce’s “On a New List of Categories” of 1867, a groundbreaking historical alternative to Kantian philosophy, and ending with the first sustained and systematic presentation of his evolutionary metaphysics in the Monist Metaphysical Series of 1891-1893. The book features a clear introduction and informative headnotes to help readers grasp the nature and significance of Peirce’s systematic philosophy and its development.

Volume 2 provides the first comprehensive anthology of Peirce’s mature philosophy. During his later years Peirce worked unremittingly to integrate new insights and discoveries into his general system of philosophy and to make his major doctrines fully coherent within that system. A central focus of Volume 2 is Peirce’s evolving theory of signs and its application to pragmatism. Included are 31 pivotal texts, beginning with “Immortality in the Light of Synechism” (in which Peirce proposes synechism—the tendency to regard everything as continuous—as a key advance over materialism, idealism, and dualism) and ending with Peirce’s late and unfinished investigations of the relative merits of different kinds of reasoning. Peirce’s Harvard Lectures on Pragmatism and selections from A Syllabus of Certain Topics of Logic are among the texts included.

“To explain is to show the unity at the heart of the manifold.”

Volume 1 takes up Peirce’s early years and presents the seminal writings that laid the groundwork for Peirce’s future studies in logic and the sign theory of cognition.

The volume opens with a sampling of the more philosophical compositions Peirce wrote during his last three years at Harvard College, from 1857 to 1859—essays that reveal a variety of nascent themes being explored by a precocious young man busy initiating himself to the methods of logical argumentation and rigorous expression while reading such works as Schiller’s Aesthetic Letters and Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Beneath his exploration of esthetic, moral, and psychological topics, Peirce already manifests a penchant for working out the logical structures that underlie them. This includes especially his attempts to improve upon and extend Kant’s list of categories. His assiduous reading of Kant, tempered by his father Benjamin’s prodding questions and by his own training in scientific reasoning (as in chemistry) and his growing experience in field research, turns Peirce into a metaphysician eager to transcend at once transcendentalism (an abuse of psychology), rationalism (an abuse of logic), and dialectics (an abuse of dogmatism) thanks to the adoption of a trusting fideism that does not seek to justify what needs no critical justification nor seeks to doubt what needs no skeptical dismissal. Such philosophical growth occurs notably in the 1861–62 “Treatise on Metaphysics,” a daring piece of innovative speculation for a thinker in his early twenties.

The core of Volume 1 consists of two series of lectures: the nine extant Harvard Lectures of February-May 1865 on “The Logic of Science,” and the ten extant Lowell Lectures of September–November 1866 on “The Logic of Science; or Induction and Hypothesis.” Those sets of lectures exhibit a broadening command of the history of logic and philosophy.

Already well read in Aristotle’s major works, Peirce in the Harvard Lectures shows familiarity with the major thinkers of the modern period and has begun reading medieval treatises in logic with uncommon interest. Right away Peirce militates in favor of an “unpsychological view of logic” and argues powerfully about the advantages of doing so, partly on the basis of fundamentally semiotic considerations. He studies the intricacies of the interplay between extension and comprehension and their connection with different types of signs and syllogistic reasoning. He shares his cutting-edge forays into Boolean algebra and illustrates the benefits of its symbolical notation for the analysis of intricate propositions, quantified or not. He studies induction with the help of Whewell, Mill, and Comte, and identifies the insufficiencies of their positions. He turns back to Kant and grapples with the distinction between analytic and synthetic judgments, and between a priori and a posteriori knowledge. And he puzzles again about Kant’s table of the functions of judgment and criticizes them on the basis of new logical distinctions. The last Harvard lectures see Peirce return to induction, and also to hypothesis, and display multiple analyses of those inferences in a syllogistic context as well as from the standpoint of the logical quantity of propositions. A definite trichotomic method gets deeply rooted in those lectures, a direct consequence of Peirce’s natural attraction to the fundamental patterns of logical structures.

Many texts at the center of Volume 1 help trace out Peirce’s progress in framing a new theory of categories, a theory that sees him both redefine the very notion of category and work out the logical methodology in identifying and testing any concept that would be a candidate for such an elementary status among conceptions. Especially striking is Peirce’s early conviction that the method that discovers categories cannot be deductive, a priori, or transcendental, but must be inductive. Equally fascinating is his framing the categories as the fundamental logical steps that govern the passage from substance to being, a passage that can only be made out by navigating it back from being to substance.

In the Lowell Lectures, Peirce reprises all the themes of his Harvard Lectures, taking advantage of one year and a half of considerable further reading and logical research. He classifies all the forms of deductive reasoning and takes up Aristotelian and Theophrastean syllogisms. He tests the extent to which syllogistic can accommodate relative predicates and mathematical demonstrations. He returns to induction, but now explores it in the context of the calculus of probabilities, and also in the context of a criticism of J. S. Mill’s conception of the uniformity of nature. He develops his information theory based on both the multiplication of the extension and comprehension of a proposition and on the conception of the interpretant as an equivalent representation. He presents publicly for the first time (in the non-extant lecture 8) his new list of three categories (within the passage from substance to being), and returns to it in the ninth lecture in considerable detail. And he vividly suggests how logic can apply to metaphysics.

The volume closes with Peirce’s important “Memoranda Concerning the Aristotelean Syllogism,” in which he demonstrates that no syllogism of the second or third figure can be reduced to the first figure, and with [“On a Method of Searching for the Categories”], the most extensive (and illuminating) draft of the 1867 essay “On a New List of Categories.”

“A certain child who is rather backward in learning to speak . . . has got to use three words only; and what are these? Name, story, and matter. . . . Already he has made his list of categories, which is the principal part of any philosophy.”

| Preface | xi |

| Acknowledgments | xiv |

| Introduction |

xv |

| 1. My Life written for the Class-Book | 1 |

| 2. Private Thoughts principally on the conduct of life | 4 |

| 3. The Sense of Beauty never furthered the Performance of a single Act of Duty | 10 |

| 4. Raphael and Michael Angelo compared as men | 13 |

| 5. A Scientific book of Synonyms | 17 |

| 6. Think Again! | 20 |

| 7. Analysis of Genius | 25 |

| 8. The Axioms of Intuition. After Kant | 31 |

|

THREE ESSAYS ON INFINITY AND GOD |

|

| 9. An essay on the Limits of Religious thought written to prove that we can reason upon the nature of God | 37 |

| 10. [The Conception of Infinity] | 40 |

| 11. Why we can Reason on the Infinite | 42 |

| 12. Proof of the Infinite Nature of the Creator | 44 |

| 13. I, IT, and THOU: A book giving Instruction in some of the Elements of Thought | 45 |

| 14. The Modus of the IT | 47 |

| 15. Views of Chemistry: sketched for Young Ladies | 50 |

| 16. [A Treatise on Metaphysics] | 57 |

| 17. Analysis of Creation | 85 |

| 18. S P Q R | 91 |

| 19. The Chemical Theory of Interpenetration | 95 |

| 20. [The Place of Our Age in the History of Civilization] | 101 |

| 21. Letter Draft, Peirce to Pliny Earle Chase | 115 |

| 22. [Shakespearian Pronunciation] | 117 |

| 23. Analysis of the Ego | 144 |

| 24. A Treatise of the Major Premisses of Natural Science | 152 |

| 25. On the Doctrine of Immediate Perception | 153 |

| 26. Letter, Peirce to Francis E. Abbot | 156 |

|

ON THE LOGIC OF SCIENCE [HARVARD LECTURES OF 1865] |

|

| 27. Lecture I | 162 |

| 28. Lecture II | 175 |

| 29. Lecture III | 189 |

| 30. Lecture on the Theories of Whewell, Mill, and Compte | 205 |

| 31. Lecture VI: Boole's Calculus of Logic | 223 |

| 32. Lecture on Kant | 240 |

| 33. Lecture VIII: Forms of Induction and Hypothesis | 256 |

| 34. Lecture X: Grounds of Induction | 272 |

| 35. Lecture XI | 286 |

| 36. Teleological Logic | 303 |

| 37. An Unpsychological View of Logic to which are appended some applications of the theory to Psychology and other subjects | 305 |

| 38. Logic of the Sciences | 322 |

| 39. [The Logic Notebook] | 337 |

| 40. Logic Chapter I | 351 |

|

THE LOGIC OF SCIENCE; OR, INDUCTION AND HYPOTHESIS [LOWELL LECTURES OF 1866] |

|

| 41. Lecture I | 358 |

| 42. Lecture II | 376 |

| 43. Lecture III | 393 |

| 44. Lecture IV | 407 |

| 45. Lecture V | 423 |

| 46. [Lecture VI] | 440 |

| 47. Lecture VII | 454 |

| 48. Lecture IX | 471 |

| 49. Lecture X | 488 |

| 50. Lecture XI | 490 |

| 51. Memoranda Concerning the Aristotelean Syllogism | 505 |

| 52. [On a Method of Searching for the Categories] | 515 |

|

APPENDIX |

|

| 53. [Diagram of the IT] | 530 |

| Editorial Notes | 531 |

| Bibliography of Peirce’s References | 564 |

| Chronological List, 1849-1866 | 569 |

| Essay on Editorial Method | 578 |

| Explanation of Symbols | 586 |

| Textual Notes | 588 |

| Emendations | 591 |

| Word Division | 685 |

| Index | 688 |

When Peirce graduated from Harvard College in 1859, he was not yet twenty. Shortly before graduation, each member of his class wrote an entry in the Harvard Class Book of 1859. Peirce’s was a humorous autobiography-in-miniature, with a sub-entry for each of the years from 1839 through 1859. The last was: "1859. Wondered what I would do in life." In a private notebook, "My Life written for the Class-Book" is continued through 1861. The last sub-entry reads: "1861. No longer wondered what I would do in life but defined my object." What was the reason for the wonder of 1859, and what had happened by 1861 to dispel that wonder and define the object?

In the male line, Peirce was descended from a John Pers (ca. 1588-1661) who came from Norwich, England, in 1637, and settled in Watertown, Massachusetts. For four generations, the Peirces were craftsmen, shopkeepers, or farmers. Then Jerathmiel (1747-1827) married Sarah Ropes, settled in Salem, entered the East India shipping trade, prospered, and built the elegant Peirce-Nichols house at 80 Federal Street. His son Benjamin (1778-1831) graduated from Harvard College, married Lydia Ropes Nichols, entered the shipping trade with his father, became a state senator, and, when Salem's shipping trade declined, became Librarian at Harvard, published a four-volume Catalogue of the library's holdings, and wrote a history of the university, which was published shortly after his death. His son Benjamin (1809-1880) graduated from Harvard College in 1829, taught for a time at the Round Hill School at Northampton, Massachusetts, and married Sarah Hunt Mills, daughter of Elijah Hunt Mills, a lawyer, co-founder of a law school there, and immediate predecessor of Daniel Webster as United States senator from Massachusetts. This Benjamin Peirce, father of our Charles S. Peirce, became professor of astronomy and mathematics at Harvard, and was the leading American mathematician of his day. He was active in the Lazzaroni, an informal group of "beggars" for federal support of scientific research, and in the movement for a national university. He published several mathematical textbooks of high quality. His major works were Analytic Mechanics (1855-57) and Linear Associative Algebra (1870). He was president of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in 1853-54, and one of the founders of the National Academy of Sciences in 1863. Just beyond our period, he was superintendent of the U. S. Coast Survey from 1867 to 1874. His brother Charles Henry Peirce was a physician, and his sister Charlotte Elizabeth Peirce had kept school and taught privately, and was at home in German and French literature.

A sister of Benjamin Peirce’s wife married Charles Henry Davis, who after seventeen years in the Navy (1823-1840) took up residence in Cambridge, studied mathematics with Benjamin, joined the Coast Survey, and in 1849 became the first superintendent of the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac.

Benjamin and Sarah had five children: James Mills (1834-1906), Charles Sanders (1839-1914), Benjamin Mills (1844-1870), Helen Huntington (1845-1923), and Herbert Henry Davis (1849-1916). James Mills (Jem), after graduating from Harvard in 1853, spent a year in the Law School, was tutor in mathematics for several years, graduated from the Divinity School in 1859, spent two years in the ministry, returned to the teaching of mathematics, and eventually succeeded to his father's professorship. Benjamin Mills, after graduating from Harvard in 1865, studied at the Paris School of Mines and later at the Lawrence Scientific School, became a mining engineer, and compiled A Report on the Resources of Iceland and Greenland, which was published by the U.S. State Department in 1868; but he died early in 1870 at Ishpeming in northern Michigan. Helen married William Rogers Ellis, who went into the rolling mill business and eventually into real estate. Herbert, after some years in the interior decorating and other businesses, became a diplomat, was secretary of legation at the U.S. embassy in St. Petersburg, then Third Assistant Secretary of State, and later minister to Norway.

The full range of the learned professions of law, medicine, divinity, and higher education, as well as business, engineering, politics, and diplomacy, was represented in the immediate family or by near relatives. Literature, the theater, and other arts were cherished if not represented. Benjamin Peirce, Charles's father, was a member of the Saturday Club, along with Emerson, Longfellow, Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and other literary figures. The Peirces were devotees of the theater, attended plays in Boston, and entertained actors in their home. Amateur theatricals were a common form of home entertainment. But what stood out for Charles in looking back from later years was that he had grown up in the Cambridge "scientific circle." The biologist and geologist Louis Agassiz lived but a stone's throw from the Peirces, and was a frequent visitor. Peirce, Agassiz, and Davis were leading members of the Cambridge Scientific Club. That club had at least fifteen meetings in the Peirce home before Charles defined his object, and another five during the years 1861-66. The Cambridge Astronomical Society (1854-57), which met every two weeks, began with Benjamin Peirce as president and Joseph Winlock as recording secretary. It was succeeded by a Mathematics Club presided over by Benjamin Peirce, which met on Wednesday afternoons for several years. It was attended by all the members of the Nautical Almanac staff. To that club Charles himself presented a paper on the four-color problem in the 1860s.

The items in the Class Book entry that shed most light on Charles's intellectual development are all extra-curricular: (1) "taking up the subject of Chemistry" (1847); (2) "Wrote a 'History of Chemistry'" (1850); (3) "Worked at Mathematics for about six months" (1854); (4) "Read Schiller's AEsthetic Letters and began the study of Kant" (1855).

We begin where Charles began, with chemistry. His father was one of the moving spirits behind the establishment within Harvard University of the Lawrence Scientific School in 1847. Eben Norton Horsford had then recently returned from two years at Giessen studying chemistry under Liebig, who combined laboratory instruction with demonstration experiments during lectures. To Liebig more than to anybody else it was due that the experimental method of teaching was more highly developed in chemistry than in any other science, so that the study of chemistry offered at that time the best entry into experimental science in general. Horsford was now made professor of chemistry in the Lawrence Scientific School, where he established, on the Liebig model, the first laboratory in America for analytical chemistry. Charles's uncle, Charles Henry Peirce, until then a practicing physician in Salem, became Horsford's assistant and was encouraged by him to translate Stockhardt's Die Schule der Chemie for textbook use. Charles's aunt, Charlotte Elizabeth Peirce, whose German was excellent, did most of the actual work of translation. During the years in which the chemical laboratory was being established and the translation was in progress, Charles's uncle and aunt helped him set up a private laboratory at home and work his way through Liebig's hundred bottles of qualitative analysis. In 1850, when the translation appeared, Charles, then eleven, wrote a "History of Chemistry" (which has not been found) . In the same year, his uncle became federal inspector of drugs for the port of Boston, and two years later, in 1852, published Examinations of Drugs, Medicines, Chemicals, Etc., as to their Purity and Adulterations, giving some of the results of his official labors. Not long before Charles entered Harvard College in 1855, his uncle died, and Charles inherited his chemical and medical library. Charles's college teacher of chemistry was Josiah P. Cooke, the initiator of laboratory instruction at the undergraduate level. The textbook he used was Stockhardt's, as translated by Charles's aunt and uncle under the title Principles of Chemistry, Illustrated by Simple Experiments.

One episode not recorded in his Class Book entry, but more often recalled in later life than any that is recorded there, was that of his introduction to logic, within a week or two of his twelfth birthday, in 1851. His older brother Jem was about to enter upon his junior year at Harvard College and had bought his textbooks for the year. Among them was Whately's Elements of Logic. Charles dropped into Jem's room, picked up the Whately, asked what logic was, got a simple answer, stretched himself on the carpet with the book open before him, and over a period of several days absorbed its contents. Since that time, he often said late in life, it had never been possible for him to think of anything, including even chemistry, except as an exercise in logic. And so far as he knew, he was the only man since the Middle Ages who had completely devoted his life to logic.

In his freshman year at college, Charles began intensive private study of philosophy with Schiller's Aesthetic Letters. From that he moved on to Kant's Critic of the Pure Reason. In his later college years, while continuing with Kant, he added modern British philosophy. In his junior year, he had to recite on Whately's Elements of Logic, as Jem had done six years before him. But all the while, as he later said, he "retained . . . a decided preference for chemistry," and it was taken for granted in the family that he was headed for a career in that science. The obvious next step after graduating would have been to enter the Lawrence Scientific School. But he felt the need of experience at earning his own living, and he had suffered so from ill health during his senior year that an interval of outdoor employment in science seemed desirable before he proceeded further. His father's friend, Alexander Dallas Bache, superintendent of the Coast Survey, offered him a place in his own field party in Maine in the fall of 1859, and in another field party around the delta of the Mississippi in the winter and spring of 1860. In early August 1859, before joining Bache's party, Charles spent a week at Springfield reporting sessions of the American Association for the Advancement of Science for six issues of the Boston Daily Evening Traveler.

On 18 December 1859 Charles wrote Jem, who was then a minister, a long letter from Pascagoula, Mississippi, in which he sought Jem's counsel. A man's first business, thought Charles, is to earn a living for himself—and for his family if he has any. Scientific research is for such leisure as that may leave him; society cannot be expected to pay for what it may have for nothing. It would appear, then, that his wondering in the Class Book what he would do in life meant wondering how he would earn a living, whether he would marry, what leisure he would have for science and for the logic of science. Jem replied at great length on 10 January. Society does pay for science, he wrote, at least if the scientific man has a practical side to his profession. And if one has a strong preference for science one will never be happy in any other occupation. "I have often thought what a fine thing it would be if you & Benjy & I should go into different departments of science: Chemistry, Natural History, & Mathematics."

During Charles's absence in Maine and Louisiana, Darwin's Origin of Species appeared, and also a separate edition of Agassiz's Essay on Classification. Chemistry was an experimental but also a classificatory science. Biology was the chief other classificatory science. The differences between these two sciences were being brought into focus by the controversy between supporters of Darwin and supporters of Agassiz. In the latter half of 1860, while serving as proctor and tutor at Harvard College, Charles was for six months a private student of Agassiz's, to learn his method of classification. One of the tasks that Agassiz set him was sorting out fossil brachiopods.

In the spring of 1861 Charles at last entered the Lawrence Scientific School. Two and a half years later he graduated as a summa cum laude Bachelor of Science in Chemistry. But during his first term the Civil War had begun, and his father had lost, by resignation, the computing aide who assisted him in his chief service to the Coast Survey, that of determining the longitudes of American in relation to European stations from occultations of the Pleiades by the moon. Charles asked his father to obtain that appointment for him. His father wrote Superintendent Bache that he had at first urged his son to "keep to his profession and wait until he could get money by his chemistry—to which he replied that he wants to get the means to buy books and apparatus and devote himself longer to the study of his profession." Bache authorized Charles's appointment as aide beginning 1 July 1861, and he was launched on the career that occupied his next thirty and a half years and took him from chemistry into astronomy, geodesy, metrology, spectroscopy, and other sciences. Some measure of his attainments in them may be found in the facts that his father proposed him for the chair of physics at The Johns Hopkins University to which Henry Augustus Rowland was appointed, and that he was the first modern experimental psychologist on the American continent.

Throughout those thirty and a half years and on beyond them, however, when he had occasion to state his profession, or even his occupation, he continued to call himself a chemist. His first professional publication, in 1863 at the age of twenty-three, was on "The Chemical Theory of Interpenetration." In later years he found in Mendeleev's work on the periodic law and table of the elements the most complete illustration of the methods of inductive science. And he took satisfaction in having, in June 1869, when he was not yet thirty, published a table of the elements that went far in Mendeleev's direction, before Mendeleev's announcement of the law, a little earlier in the same year, became known in western Europe and America. At that year's meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science it was remarked that Peirce "had greatly added to the illustration of the fact of pairing by representing in a diagram the elements in positions determined by ordinates representing the atomic numbers."

At the end of 1891, after thirty-one and a half years in the service of the Coast and Geodetic Survey, his appointment was terminated, and he set up in private practice as a chemical engineer, thereby returning to the profession to which he had committed himself before he entered the Survey, and from which his career in the Survey had been in some sense a diversion.

It was not until 1906, in the first edition of American Men of Science, that for the first time in any biographical reference work, logic was named as the chief field of his investigations. In the first five editions of Who's Who in America, from 1899-1900 through 1908-1909, his profession appears as that of lecturer and engineer. In the sixth edition, that of 1910-1911, for the first time in any reference work, it appears as that of logician. Only after his death did he begin to be called a philosopher.

How then had he defined his object when in 1861 he no longer wondered what he would do in life? There are no letters or other records of that year from which an explicit, complete, and confident answer can be drawn. We are reduced therefore to piecing together the few indications we have from that time, and filling them out from subsequent events and from Peirce’s later recollections and autobiographical remarks.

Chemistry at that time offered the best entry into experimental science in general, and was therefore the best field in which to do one's postgraduate work, even if one intended to move on to other sciences and, by way of the sciences, to the logic of science and to logic as a whole. Moreover, chemical engineering was then the most promising field in which to make a living by science, if one had no opportunity to do so by pure science or by logic.

That Peirce had no intention of confining himself to chemistry appears from his spending six months in private study of zoological classification under Agassiz before entering the Lawrence Scientific School. It appears also from his oration on "The Place of Our Age in the History of Civilization" (1863) and from "Shakespearian Pronunciation" (1864). It becomes fully evident from the two courses of lectures on the logic of science which he delivered in the spring of 1865 and the fall of 1866, and from the course on the history of logic in Great Britain which he delivered in 1869-70. The first and third of these courses were "University Lectures" at Harvard, each a part of an extensive program of such courses intended primarily for graduates of the college, and each offered but once. One of the men who attended the third course, along with others given in 1869-70, described them many years later as "The Germ of the Graduate School." Both in the university and in the Lowell Institute, in which the second course was given, each lecturer was expected to devote his lectures to the field and topics of his greatest competence, or on which he had most to offer that was new.

The most striking evidence, however, may be found in Peirce’s election in January 1867 to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and in April 1877 to the National Academy of Sciences. To the former academy, in March, April, May, September, and November 1867 he presented five papers, all in logic, and all his subsequent papers in the Proceedings and Memoirs of that academy were in logic. Before his election to the National Academy, he was asked to send a list of his scientific papers, but sent instead the titles of four of his papers in logic and said he wished to be judged by those alone; and after his election he wrote to the secretary expressing his gratification at the implied recognition of logic as a science. Of the thirty-four papers he presented to the National Academy from 1878 to 1911, nearly a third were in logic. Others were in mathematics, physics, geodesy, spectroscopy, and experimental psychology; but in none of these fields did the number approach that in logic.

In connection with Peirce’s private study of zoological classification under Agassiz, we mentioned that biology, like chemistry, is a classificatory science. We may add now that logic also is a classificatory science; that in Peirce’s first series of published papers in logic, which will appear early in our second volume, the second paper was called "On a Natural Classification of Arguments"; that his first privately printed paper in logic, his "Memoranda Concerning the Aristotelean Syllogism," near the end of the present volume, contained his first original contribution to the classification of arguments; that he at that time conceived logic to be a branch of semeiotic, the general theory of signs; that he later adopted a much broader conception of logic in which, if it was not coextensive with semeiotic, it was so nearly so that for some time to come logicians were likely to be the chief cultivators of the general theory of signs; and that, in his own lifetime as a whole, he devoted more labor to the classification of signs than to any other single field of research. His pragmatism, for example, lay wholly within its scope.

How then had Peirce defined his object in 1861? Somewhat as follows, we may safely infer from all the evidence, early and late. In mathematics and in as wide a range of the sciences, physical and psychical, as possible—including the history of science and of mathematics—he would reach the point of carrying out and publishing original researches. He would begin with chemistry, the open sesame to the experimental sciences. He would earn his living by science as far as possible, so that his hours of employment as well as of leisure should further his object. He would prefer employment that gave him scope for diversity of researches over a period of years. His researches in sciences other than logic would in the first place be for the sake of those sciences themselves, but all would be brought to a second focus in logic, as including both the logic of mathematics and the logic of science, and eventually as including the general theory of signs. By bringing logic (and thereby metaphysics) abreast of the exact sciences in which he had been bred, he would at the same time serve the several sciences at a second and higher level.

But why should Peirce have supposed that by first making positive contributions to mathematics and to a wide range of the sciences he would then become a better contributor to logic? Because a scientific logic must take full account of the reasonings of mathematics and the sciences and because the traditional logic has failed to do so. It has failed in part because mathematicians who are not logicians, and logicians who are not mathematicians, are not fully competent to analyze the reasonings of mathematicians; and because scientists who are not logicians, and logicians who are not scientists, or who are scientists in only a single science or in but two or three closely related sciences, are not fully competent to analyze the reasonings of scientists.

If we think of the literature of the logic of science as including on the one hand Descartes's Discourse on the Method of Rightly Conducting the Reason and Searching for the Truth in the Sciences; and on the other Bacon's Novum Organum and Whewell's Novum Organon Renovatum it will seem at least an hypothesis worth trying that a logician's ability to contribute to the logic of science may be enhanced by extending the range of his scientific researches. For Whewell had done just that, and had also written and published a three-volume History of the Inductive Sciences (1837), before publishing his two-volume Philosophy of the Inductive Sciences, Founded Upon Their History (1840). His Novum Organon Renovatum (1858) was Part 2 of the third edition of the latter work.

In his 1865 Harvard University Lectures on the Logic of Science, in the present volume, Peirce speaks of Whewell as "man of science," "historian of science," and "the most profound writer upon our subject." But he speaks at much greater length in the lecture on Whewell in his Harvard University Lectures of 1869 on the British Logicians, which will appear in volume 2. That may be our best evidence of the way in which Peirce had defined his object in life.

But whether in fact, and to what extent, Peirce’s contributions to the logic of science can be traced to the diversification of his scientific researches is still to be determined, and it is one of the aims of the present edition of his writings to open the way toward answering that question .

When Bacon gave the title Novum Organum to the second part of his major work, The Great Instauration, and when Whewell gave the title Novum Organon Renovatum to the second part of his major work in its third edition, they thereby claimed to be making great advances in logic, the science founded by Aristotle in his Organon Advances not in the whole range of the Organon, to be sure, but only in the logic of science; more exactly, in the theory of how the inductive and especially the experimental sciences are advanced. But the Organon itself began with a treatise on Categories, in which ten were listed and discussed; and Peirce began where the Organon began.

Aristotle's categories were substance, quantity, quality, relation, place, time, position, state, action, and passion. Many lists differing more or less from his were drawn up by later logicians. In Peirce’s time the best known of these were Kant's short list of twelve and the long list of Hegel's Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences. Bacon had used the phrase "Transcendentals, or Adventitious Conditions of Essences." Whewell used the phrase "Fundamental Ideas" but offered no inclusive list; it was for the future progress of the sciences to evolve one.

Looking back from 1898, Peirce wrote: "In the early sixties I was a passionate devotee of Kant, at least as regards the Transcendental Analytic in the Critic of the Pure Reason. I believed more implicitly in the two tables of the Functions of Judgment and the Categories than if they had been brought down from Sinai." In Meiklejohn's translation of 1855, which Peirce owned and used beginning not later than 1856, the two tables appear six pages apart. To facilitate comparison, we present them here in parallel columns.

[TABLE OF JUDGMENTS]

I. Quantity of judgments

Universal

II. Quality

Affirmative

III. Relation

Categorical

IV. Modality

Problematical

TABLE OF THE CATEGORIES

I. Of Quantity

Unity

II. Of Quality

Reality

Of Inherence and Subsistence (substantia et accidens)

IV. Of Modality

Possibility-Impossibility

For the present we shall confine our attention to the Table of the Categories. It is obvious at once that three of Aristotle's ten categories appear as heads of three of Kant's four triads, and two or three others appear in modified forms within them. Hegel remarked that the four headings that Kant used for his triads were in fact categories of a more general nature. Kant himself had remarked that in each triad the third category arises from the combination of the second with the first. Peirce will later make a similar observation about Hegel's three stages of thought, which he will call Hegel's universal categories, as distinguished from the particular categories of the Encyclopedia. He will also say that his own three categories correspond both to Hegel's universal categories and to the three categories implicit in each of Kant's four triads.

Volume 2 will include the five papers in logic that Peirce presented to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1867. The third of them offered the following "New List of Categories:

BEING,

Quality

(Reference to a Ground),

Relation

(Reference to a Correlate),

Representation (Reference to an

Interpretant),

SUBSTANCE.

Peirce soon reduced the five to three by sloughing off Being and Substance. We note at once that two of Aristotle's categories reappear in Peirce’s triad as well as in the headings of two of Kant's triads. Only representation is new. But that is novelty enough. It is the first list of categories that opens the way to making the general theory of signs fundamental in logic, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Peirce’s paper "On a New List of Categories" was presented to the academy on 14 May 1867. In his private Logic Notebook, on 23 March, Peirce wrote:

"I cannot explain the deep emotion with which I open this book again. Here I write but never after read what I have written for what I write is done in the process of forming a conception. Yet I cannot forget that here are the germs of the theory of the categories which is (if anything is) the gift I make to the world. That is my child. In it I shall live when oblivion has me—my body."

And thirty-eight years later, in a draft of a letter to Mario Calderoni, he could still write that

"on May 14, 1867, after three years of almost insanely concentrated thought, hardly interrupted even by sleep, I produced my one contribution to philosophy in the "New List of Categories." My three categories are nothing but Hegel's three grades of thinking. I know very well that there are other categories, those which Hegel calls by that name. But I never succeeded in satisfying myself with any list of them."

Readers of the present volume will bring to it numerous questions the editors cannot hope to anticipate. It seems safe to assume, however, that readers wishing to understand Peirce on his own terms will be more numerous than those who approach him with the same particular question or group of questions of their own. On that assumption, our primary aim in volume 1 has been to include in their chronological places the writings in which the reader can trace the steps by which Peirce arrived at his new list of categories, and at the first published forms of his general theory of signs and his sign theory of cognition; and in subsequent volumes the steps by which he moved through successive modifications of all three toward his last great undertaking, "A System of Logic, considered as Semeiotic." But we include every paper of comparable originality, whether directly relevant or not to this primary aim. No range of his work will be left unrepresented.

We turn now to a few of the less obvious early episodes in the search for the categories within the period of the present volume.

Charles Russell Lowell (eldest brother of the poet James Russell Lowell) and his wife, Anna Cabot Jackson Lowell, were neighbors of the Peirces. Their home was a center of hospitality. It was there that Peirce met Chauncey Wright, the ablest philosopher with whom he was personally acquainted in his early years. Shortly before he entered college, Mrs. Lowell had lent Peirce a copy of John Weiss translation of The Aesthetic Letters of Friedrich Schiller. As a result of alphabetic seating in their college classes, he and Horatio Paine ("noble-hearted, sterling-charactered," "almost the only real companion I have ever had") became intimate friends. Schiller's book interested them more than anything they were required to read in college, and they "spent every afternoon for long months upon it, picking the matter to pieces as well as we boys knew how to do." From Schiller they proceeded to Kant's Critic of the Pure Reason (as Peirce later rendered the title), and Peirce continued the study of the Critic until he almost "knew it by heart in both editions."

One of the assigned "themes" in their sophomore year was on a sentence from Ruskin's Modern Painters: "It has been said by Schiller in his letters on aesthetic culture that the sense of beauty never farthered the performance of a single duty." Peirce was well prepared to defend Schiller against Ruskin's misunderstanding. He gives an account of the three impulses distinguished by Schiller—the Formtrieb, Stofftrieb, and Spieltrieb. In response to a comment on his theme by their professor, Francis J. Child, Peirce added at the end: "I should say that these were the I impulse and faculty, and the IT impulse and faculty; and also the THOU impulse and faculty which (it seems to me) is what Schiller regards as that of beauty."

Readers familiar with Martin Buber's I and Thou will be struck by the prominence of I, IT, and THOU in the early stages of Peirce’s search for the categories. If Kant's categories come in triads, and if the Hegelian dialectic moves in triads of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis, and if Schiller finds only three fundamental drives or faculties, we may well be moved to try the hypothesis that Aristotle's ten categories and Kant's twelve are reducible to three. If, further, we expect the categories to manifest themselves in language as well as in thought, it may strike us that in the language we speak there is nothing more prominent than the three persons of the verb and the corresponding pronouns. (Some readers will recall at this point that Peirce later held that nouns are substitutes for pronouns, not, as their names assume, pronouns for nouns.)

If we then try finding our categories in, or deriving them from, the personal pronouns, our first trials are likely to take them in the order I, THOU, IT; and that is what Peirce does in his earliest surviving table, as well as in a theme comparing Michelangelo and Raphael, both written in 1857. In the table, he is already connecting his pronominal categories with Kant's triads; for that purpose he changes the order of the second and third categories in two of Kant's triads, and we wonder why he does not do so in the third as well.

By January 1859, if not earlier, he has settled on the order I, IT, THOU. In that month he begins a book on "The Natural History of Words," in which the first page of text reads:

THE PERSONS

I

I me

The

first person, the ego, the I, the Me, subject, self

Not-I non-ego

Subjective, my, mine

to me

IT

He him she her it they them, third person

Being, Thing, to ov thing in itself,

noumenon

be is are were was been

THOU

Thou, thee, ye, you; 0!

Second person,

thine, yours, thy,

your.

It is assumed throughout that semeiotic, the general theory of signs, including words and other symbols, is a classificatory science, like chemistry and biology; and we are starting with words, and, among words, with those associated with the three persons of the Verb, and with the names I, THOU, and IT for those persons. It is made emphatic that the logical or categorical order of these names is different from the traditional grammatical order of the persons, but the reason for the difference is not stated.

On 1 June 1859 Peirce constructs an octagonal table of subcategories of the IT, including all of Kant's categories with some puzzling alterations. Kant's first triad appears as Infinite Qualities of Quantity, his second as Influxual Dependencies of Quality, his third as Necessary Modes of Dependence, and his fourth as Perfect Degrees of Modality. These are followed by four other triads, the last of which brings us back to Kant's first.

In the spring of 1861 Peirce begins a book entitled, "I, IT, and THOU." "I here, for the first time," he writes, "begin a developement of these conceptions. . . . THOU is an IT in which there is another I. I looks in, It looks out, Thou looks through, out and in again." For the first time, it becomes emphatic and clear that THOU presupposes IT, and IT presupposes I. That is the reason for the difference between the categorical and the grammatical order.

In the next year, 1862, William James writes in one of his notebooks:

"The thou idea, as

Pierce calls it, dominates an entire realm of mental phenomena,

embracing poetry, all direct intuition of nature, scientific

instincts, relations of man to man, morality &c.

"All analysis must be into a triad;

me & it require the complement of thou."

In his oration on "The Place of Our Age in the History of Civilization," delivered at a reunion of the Cambridge High School Association on 12 November 1863 and published in the Cambridge Chronicle, Peirce says: "First there was the egotistical stage when man arbitrarily imagined perfection, now is the idistical stage when he observes it. Hereafter must be the more glorious tuistical stage when he shall be in communion with her."

In 1891 Peirce defines tuism for the Century Dictionary as "The doctrine that all thought is addressed to a second person, or to one's future self as to a second person." The Oxford English Dictionary later quotes this definition in its own entry. There and in its illeism entry, it is recorded that Coleridge had used the terms egotism, illeism, and tuism, but not in any systematic or technical way.

Though by 1867 Peirce has abandoned I, IT, and THOU as names for his categories, it is only because he has found better technical terms for what he has meant by those more colloquial ones.

The main substance of the present volume is in the two series of lectures on the logic of science—the Harvard University Lectures in the spring of 1865 and the Lowell Institute Lectures in the fall of 1866. Though a few extracts from both series have been published, the present volume contains for the first time as near an approach to a complete letterpress edition of the two as the surviving manuscripts make possible. It also enables us to attend both series with the benefit of prior acquaintance with several years of the young lecturer's life and work, and thereby prepares us for the second and subsequent volumes .

We are tempted to say on the one hand that in these two courses Peirce has for the most part unfolded his thoughts before us with such fullness that any editorial introduction would be superfluous, and on the other hand that an adequate introduction will be possible only after several years of detailed examination by Peirce scholars and by historians of logic.

If some readers find his metaphysics more interesting than his logic, we invite their attention to the last of the Lowell Lectures, on the advantages of "adopting our logic as our metaphysics." If we learn our logic from Peirce, we shall thereby be led, for example, not only to the sign theory of cognition but also to the sign (more exactly the symbol) theory of man, and to a metaphysics akin to trinitarian theology. Near the end, the lecturer is saying:

"Here, therefore, we have a divine trinity of the object, interpretant, and ground. . . . In many respects, this trinity agrees with the Christian trinity; indeed I am not aware that there are any points of disagreement. The interpretant is evidently the Divine Logos or word; and if our former guess that a Reference to an interpretant is Paternity be right, this would be also the Son of God. The ground, being that partaking of which is requisite to any communication with the Symbol, corresponds in its function to the Holy Spirit."

This becomes intelligible only in the light of biographical details more intimate than those we have so far cited.

Peirce was brought up a Unitarian. The family attended services at the College Chapel. Frederic Dan Huntington's appointment as Plummer Professor of Christian Morals and Preacher to the College began with Peirce’s freshman year and continued a year beyond his graduation It was under Huntington that Peirce in his freshman year studied Richard Whately's Lessons on Morals and Christian Evidences. Huntington was a Unitarian, but he became an Episcopalian early in 1860 and therefore resigned his professorship. (He later became the first Episcopal bishop of Central New York, with diocesan headquarters at Syracuse.)

Among the Harvard classmates of Peirce’s father was Charles Fay, who became an Episcopalian clergyman, married a daughter of John Henry Hopkins, the first Episcopal bishop of Vermont, and since 1848 had been rector of St. Luke's Episcopal Church at St. Albans, Vermont. The eldest daughter of the Fays, Harriet Melusina, usually called Zina, was a passionate feminist deeply concerned from adoescence about the role of women in society. In the summer of 1859 she arrived at an interpretation of the doctrine of the trinity according to which the Holy Spirit is the feminine element in the triune god-head: "a Divine Eternal Trinity of Father, Mother and Only Son—the 'Mother' being veiled throughout the Scriptures under the terms 'The Spirit,' 'Wisdom,' 'The Holy Ghost,' 'The Comforter,' and 'The Woman clothed with the sun and crowned with the stars and with the moon under her feet'."

After her mother's death in 1856, Zina had been in correspondence with Ralph Waldo Emerson, and it was on his advice that in the fall of 1859 she entered the Agassiz School for Young Ladies, in the Agassiz home just across Quincy Street from the Peirces. Perhaps it was there that Charles and Zina met, in the winter of 1860-61 if not earlier. He made his first formal call upon her in January 1861. Several of his metaphysical writings from 1861 onwards are marked "For Z. F.," and probably most if not all of them were written for her. In the summer of 1861 he made the first of several extended visits to Zina and her family in St. Albans. His "Views of Chemistry: sketched for Young Ladies," written for Zina and her younger sisters, were begun during that visit. When he defined his object in that year, it probably included marriage with her. By the spring of 1862 they were engaged. It seemed to his parents that for the first time he was taking religion seriously. In the evening of 24 July, in the chapel of the Vermont Episcopal Institute in Burlington, in the presence of Zina and several members of her family, Charles was confirmed by her grandfather, Bishop Hopkins. On 16 October Charles and Zina were married by her father at St. Luke's in St. Albans. (They had no children. After fourteen years together, she separated herself from him. He divorced her in 1883 and took a second wife. Zina did not remarry.)

Peirce’s conversion to Episcopalianism entailed of course a conversion from unitarianism to trinitarianism. Though not always an active communicant, he remained an Episcopalian and a trinitarian to the end of his life. And as late as 1907 we find a distant echo of Zina's feminist version of the trinity. In outlining a draft of what turned out to be his best account of pragmatism within the framework of his general theory of signs, he then wrote: "A Sign mediates between its Object and its Meaning. . . Object the father, sign the mother of meaning." That is, he might have added, of their son, the Interpretant.

Though Peirce’s categories are meant to be universally applicable, and he did so apply them, his most frequent single application of all three together is in the definition of a sign. In his many definifions, early and late, the nearest to a constant is that a sign is a first something so determined (limited, specialized) by a second something, called its object, as to determine a third something, called its interpretant, to determination by the same object. That is, sign action or semeiosis (as distinguished from dyadic mechanical action) involves an irreducibly triadic relation between (1) a sign, (2) its object, and (3) its interpretant.

His most frequent single occasion for defining a sign is that of a logician for whom logic is "the critic of arguments" and arguments are a kind of signs. After defining a sign, his most frequent next three moves, each a reapplication of his categories, are: (1) dividing signs into icons, indexes, and symbols; (2) dividing symbols into terms, propositions, and arguments; and (3) dividing arguments into retroductions, inductions, and deductions. He is then ready for the main business of logic, that of determining the relative validity or strength of each kind of arguments.

(In the present volume, he uses "representation" and "representamen" in approximately the senses in which he will later use "sign," and by "sign" he usually means what toward the end of the volume he begins calling "index." What in this volume he calls "likeness," "copy," "image," or "analogue," he will begin calling "icon" in 1885. "Abduction" and "retroduction" are his later and more technical terms for what he here calls "hypothesis" or "inference a' posteriori." For a short while he tries "subject" and "correspondent" for what, toward the end of the volume, he begins calling "interpretant.")

Logic is for Peirce a science, and its definition must therefore place it in relation to other sciences. That calls for a classification of the sciences. No logician—no philosopher—ever attached more importance, or devoted more attention, to classifications of the sciences than Peirce did. The most general and the most familiar classification was that which John Locke, in the last chapter of his Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690), ascribed to the Greeks: [Greek] or natural science, [Greek] or moral science, and [Greek] or "the Doctrine of Signs, the most usual whereof being Words, it is aptly enough termed also [Greek], Logick." Peirce objects that, of the three kinds of signs, logic deals only with symbols, and with them only in relation to their objects, and only in respect of truth and falsity. Moreover, of the three kinds of symbols, it has little to say of terms and propositions except as they enter into arguments. So logic is at most but a third part of a third part—that is, a ninth part—of semeiotic. It might be defined as objective symbolistic.

By the mid-1880s, however, Peirce will have come to realize that logic cannot do business without icons and indexes and that it must take account of all three kinds of symbols both in themselves and in relation to their interpretants as well as in relation to their objects. In the 1890s he will distinguish a narrow sense in which logic is still concerned only with arguments and only in relation to their objects, and a broad sense in which it is coextensive with semeiotic in the sense of "the general theory of signs," leaving room for an indefinite number of more specialized semeiotic sciences. He is thus halfway back to Locke. By 1902, he will abandon the narrow sense altogether, or use Locke's term critic rather than logic as the name for it; and the semeiotic trivium will become the logical trivium of speculative grammar, critic, and speculative rhetoric or methodeutic; and by 1909 he is drafting "A System of Logic, considered as Semeiotic." It has taken him most of his productive lifetime to come all the way back to Locke. With this in mind, it should not surprise us that, over that lifetime, Peirce devoted more study than any other major logician has done to "the doctrine of signs."

Returning now to the classification of arguments, we remark that though the title of Peirce’s Harvard University Lectures of 1865 was simply "On the Logic of Science," that of his Lowell Institute Lectures of 1866 was "The Logic of Science; or, Induction and Hypothesis." The latter title would have been read at the time as if it had been written "The Logic of Science; or, Induction—and Hypothesis!" The common assumption was that the logic of mathematics was the logic of deduction, and the logic of science that of induction. Though it was obvious that the advancement of the empirical and experimental sciences depended on the forming and testing of hypotheses, hypothesis was not (and is not yet) understood as a distinct kind of inference or argument.

But Peirce’s three categories led him to expect to find three distinct kinds of arguments. (He later intimated that the chief single purpose of his work on the categories had been to have a guide to the classification of arguments.) The problem was to identify, distinguish, and name them. He began where Kant began in his major work, whose title Peirce proposed to translate "Critic of the Pure Reason"; namely, with the distinction between two kinds of "judgments": (1) analytic or explicative and (2) synthetic or ampliative. Peirce first adopted the second term of each pair. He then turned the distinction between explicative and ampliative judgments into the distinction between explicative and ampliative arguments or inferences. A possible way of coming out with three kinds instead of two was to divide one or the other into two. He would later distinguish two kinds of mathe-matical demonstration, corollarial and theorematic, but he had as yet no inkling of that. Even if he had already worked it out, the difference between them would not have seemed to him so radical as that between the two kinds of ampliative inference which he now readily found; the difference, that is, between induction more strictly speaking on the one hand, and on the other reasoning to a hypothesis that will both account for puzzling data already obtained and serve to predict results of experiments not yet tried or observations not yet made.

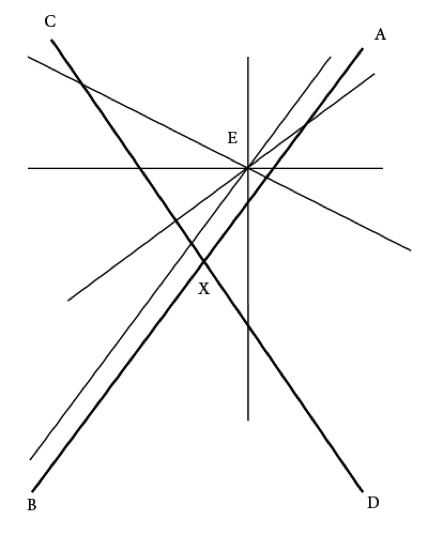

Peirce next connected explicative arguments with the first of the three Aristotelian figures of the syllogism, and more particularly with the mood Barbara. He then tried connecting hypothesis with the second figure, and particularly with the mood Baroco; and induction with the third figure, and particularly with the mood Bocardo. In the order of the validity or strength of the three kinds of arguments, from the weakest to the strongest, the connections thus became: (1) first category, hypothesis, second figure; (2) second category, induction, third figure; (3) third category, deduction, first figure.

But connecting the three kinds of inference with the three Aristotelian figures of the syllogism was open to two lines of attack. (1) What about the fourth figure? Having adopted as his "primary conceptions" those of rule, subsumption of case, and result, Peirce rejects the fourth figure and "all its moods not as being invalid but as being indirect, and unsyllogistic." (2) But since syllogisms in the second and third figures are reducible to syllogisms in the first, must we not concur with Kant in his early tract On the False Subtlety of the Four Syllogistic Figures? That question led Peirce to his first major discovery in logic; namely, that every such reduction takes the logical form of an argument in the figure from which the reduction is made. He thought enough of this discovery to have his essay on it privately printed in time for distribution at his Lowell Lectures in November 1866, under the title Memoranda Concerning the Aristotelean Syllogism; and he mailed copies to logicians at home and abroad. Augustus De Morgan in London received his copy on 29 December 1866. By the end of the period covered by the present volume, Peirce had thus joined the small international community of professional logicians.

MAX H. FISCH

The following five corrections to the first printing have been incorporated in the second printing; the original readings are given in brackets.

paper [papers]

of [or]

reasonableness [reasonbleness]

symbols [things]

blue [red]

Emendations for the last two, which represent Peirce’s own errors, have been added on pages 640 and 661.

The following nine corrections to the second printing have been incorporated in the third printing; the original readings are given in brackets.

familiar [familar]

forms manifested . . . symbols translated

[symbols translated . . . forms manifested]

denotation [information]

Chapter [Chaper]

rests is . . . conclusion,—this [rests—is . . . conclusion. This]

hypothesis [hyopthesis]

letzterer [letzerer]

A heavy dot has been inserted, centered under the short horizontal line at the top of that page

information, [information]

Emendations for 276.19–20, 277.11–12, and 484.11, which represent Peirce’s errors, have been added on pages 639 and 676; two emendations have been removed on page 668, for correction 435.27–29.

The following five corrections to the third printing have been incorporated in the fourth printing; the original readings are given in brackets.

and [is]

that what [that that what]

that which is not what a word denotes

[which what a word denotes is not]

mortals) [mortals]

écrits [ecrits]

Emendations for the first three errata, which represent Peirce’s errors, have been added on pages 658 and 671.

but three [but the]

three elements [both]

term [proposition]

terms [propositions]

other [first]

rule [case]

and [or]

everything [every thing]

But the extension of a general term [But the comprehension of a general term]

In short, the logical extension, [In short, the logical comprehension,]

a whole of extension. [a whole of comprehension.]

dark red colour has still less extension.

[dark red colour has still less comprehension.]

An Index term is one which has no adequate comprehension; [An Index term is one which has no adequate extension;]

The year in the running head on odd pages from 65 to 83 should read 1862 instead of 1861.

“Intellectual Symbolism” [Intellectual Symbolism]

only Images à posteriori recalled [only Images à priori recalled] Peirce’s error confirmed by 62.15–16

otherwise [other wise]

The interlineation b = 0 on line 19 should have been inserted just after the fifth word of line 20, to read:

either b is zero b = 0 or

for the plant [for plant]

MS 70 (920, 919, S66) [MS 70 (920, 919)]

MS 71 (1105, 921, 919, 741, 922) [MS 71 (1105, 921, 919, 741)]

MS 92 (1156a) 1864–1871 [MS 92 (1596) 1864–1869]

“I cannot explain the deep emotion with which I open this book again. . . . I cannot forget that here are the germs of the theory of the categories which is (if anything is) the gift I make to the world. That is my child. In it I shall live when oblivion has me—my body.”

Volume 2 (1867–1871) contains some of the major philosophical and logical writings of Peirce’s entire life. His epochal “New List of Categories” of 1867, his three “cognition” articles in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy of 1868–69, and his review of the works of Berkeley in the North American Review of 1871 are now recognized as constituting the modern founding of semiotics, the general theory of signs, while providing also a new fundamental platform for philosophy itself. If we add to these the 1867 review of Venn’s Logic of Chance, the 1867–68 critique of positivism, and the 1870 memoir, “Description of a Notation for the Logic of Relatives,” and read all eight in chronological order, we can trace the early stages of Peirce’s continued effort to redefine and clarify realism by disentangling it progressively from nominalism. His other papers in logic bring improvement to Boole’s calculus of logic; provide a natural classification of arguments that revisits the figures of syllogisms and tie them to induction, hypothesis, and analogy; work out a formal logic of mathematics; and make public Peirce’s research on logical comprehension and extension. Other essays and lectures testify to Peirce’s deep study of the works of British logicians.

When Peirce was appointed assistant in the United States Coast Survey in 1867, he began an ascent that carried him during the next decade to the select ranks of leadership in science in America and to renown in the international scientific community. The focus of Peirce’s scientific work during the period of the volume 2 was astronomy, and, by arrangement with the Coast Survey, his work was conducted principally at the Harvard Observatory. Peirce was an official observer of two total eclipses of the sun during these years, the first in Kentucky in 1869 and the second in Sicily in 1870. During the several months that Peirce spent in Europe in 1870–71, he became acquainted with many leading European astronomers. In 1871 he began his observations with Harvard’s Zöllner astrophotometer, which resulted in his only published monograph, Photometric Researches, parts of which are included in Volume 3.

“Whether men really have anything in common, so that the community is to be considered as an end in itself, . . . is the most fundamental practical question in regard to every public institution the constitution of which we have it in our power to influence.”

Volume 2 contains some of the major philosophical writings of Peirce’s entire life. His "New List of Categories" of 1867, his three "cognition" articles in the Journal of Speculative Philosophy of 1868-69, and his review of the works of Berkeley in the North American Review of 1871 are now recognized as constituting the modern founding of semiotics, the general theory of signs. If we add to these the 1867 review of Venn's Logic of Chance and the 1870 memoir on the "logic of relatives," and read all seven in chronological order, we can trace the early stages of Peirce’s progress from nominalism to realism. When Peirce was appointed assistant in the United States Coast Survey in 1867, he began an ascent that carried him during the next decade to the select ranks of leadership in science in America and to renown in the international scientific community.

The focus of Peirce’s scientific work during the period of the present volume was astronomy, and, by arrangement with the Coast Survey, his work was conducted principally at the Harvard Observatory. Peirce was an official observer of two total eclipses of the sun during these years, the first in Kentucky in 1869 and the second in Sicily in 1870. During the several months that Peirce spent in Europe in 1870-71, he became acquainted with many leading European astronomers. In 1871 he began his observations with Harvard's Zollner astrophotometer, which resulted in his only published monograph, Photometric Researches, parts of which are included in Volume 5.

| Preface | xi |

| Acknowledgments | xix |

| Introduction |

xxi

|

| The Decisive Year and Its Early Consequences Max H. Fisch | xxi |

| The Journal of Speculative Philosophy Papers C. V. Delaney | xxxvi |

| The 1870 Logic of Relatives Memoir Daniel D. Merrill | xlii |

| 1. [The Logic Notebook] | 1 |

|

[THE AMERICAN ACADEMY SERIES] |

|

| 2. On an Improvement in Boole's Calculus of Logic | 12 |

| 3. On the Natural Classification of Arguments | 23 |

| 4. On a New List of Categories | 49 |

| 5. Upon the Logic of Mathematics | 59 |

| 6. Upon Logical Comprehension and Extension | 70 |

| 7. Notes | 87 |

| 8. [Venn's The Logic of Chance] | 98 |

| 9. Chapter I. One, Two, and Three | 103 |

| 10. Specimen of a Dictionary of the Terms of Logic and allied Sciences: A to ABS | 105 |

| 11. [Critique of Positivism] | 122 |

|

[THE PEIRCE-HARRIS EXCHANGE ON HEGEL] |

|

| 12. Paul Janet and Hegel, by W. T. Harris | 132 |

| 13. Letter, Peirce to W. T. Harris (24 January 1868) | 143 |

| 14. Nominalism versus Realism | 144 |

| 15. Letter, Peirce to W. T. Harris (16 March 1868) | 154 |

| 16. What is Meant by "Determined" | 155 |

| 17. Letter, Peirce to W. T. Harris (9 April 1868) | 158 |

|

[THE JOURNAL OF SPECULATIVE PHILOSOPHY SERIES] |

|

| 18. Questions on Reality | 162 |

| 19. Potentia ex Impotentia | 187 |

| 20. Letter, Peirce to W. T. Harris (30 November 1868) | 192 |

| 21. Questions Concerning Certain Faculties Claimed for Man | 193 |

| 22. Some Consequences of Four Incapacities | 211 |

| 23. Grounds of Validity of the Laws of Logic | 242 |

| 24. Professor Porter's Human Intellect | 273 |

| 25. The Pairing of the Elements | 282 |

| 26. Roscoe's Spectrum Analysis | 285 |

| 27. [The Solar Eclipse of 7 August 1869] | 290 |

| 28. Preliminary Sketch of Logic | 294 |

| 29. [The Logic Notebook] | 298 |

| 30. The English Doctrine of Ideas | 302 |

|

[LECTURES ON BRITISH LOGICIANS] |

|

| 31. Lecture I. Early nominalism and realism | 310 |

| 32. Ockam. Lecture 3 | 317 |

| 33. Whewell | 337 |

|

[PRACTICAL LOGIC] |

|

| 34. Lessons in Practical Logic | 348 |

| 35. A Practical Treatise on Logic and Methodology | 350 |

| 36. Rules of Investigation | 351 |

| 37. Practical Logic | 353 |

| 38. Chapter 2 | 356 |

| 39. Description of a Notation for the Logic of Relatives | 359 |

| 40. A System of Logic | 430 |

| 41. [Henry James's The Secret of Swedenborg] | 433 |

| 42. Notes for Lectures on Logic to be given 1st term 1870-71 | 439 |

| 43. Bain's Logic | 441 |

| 44. Letter, Peirce to W. S. Jevons | 445 |

| 45. [Augustus De Morgan] | 448 |

| 46. Of the Copulas of Algebra | 451 |

| 47. [Charles Babbage] | 457 |

|

[THE BERKELEY REVIEW] |

|

| 48. [Fraser's The Works of George Berkeley] | 462 |

| 49. [Peirce’s Berkeley Review], by Chauncey Wright | 487 |

| 50. Mr. Peirce and the Realists | 490 |

|

APPENDIX |

|

| 51. Letter, J. E. Oliver to Peirce | 492 |

| Editorial Notes | 499 |

| Bibliography of Peirce’s References | 555 |

| Chronological List, 1867-1871 | 564 |

|

TEXTUAL APPARATUS |

|

| Essay on Editorial Method | 469 |

| Explanation of Symbols | 582 |

| Textual Notes | 584 |

| Emendations | 586 |

| Word Division | 629 |

| Index | 632 |

The most decisive year of Peirce’s professional life, and one of the most eventful, was 1867.

Superintendent Bache of the Coast Survey had been incapacitated by a stroke in the summer of 1864. He died on 17 February 1867. Benjamin Peirce became the third Superintendent on 26 February and continued in that position into 1874. He retained his professorship at Harvard and, except for short stays in Washington, he conducted the business of Superintendent from Cambridge. Julius E. Hilgard served as Assistant in Charge of the Survey's Washington office. On 1 July 1867 Charles was promoted from Aide to Assistant, the rank next under that of Superintendent. He continued in that rank for twenty-four and a half years, through 31 December 1891.

National and international awareness of the Survey was extended by two related episodes beginning in 1867. A treaty with Russia for the purchase of Alaska, negotiated by Secretary of State William Henry Seward, was approved by the Senate on 9 April, but the House delayed action on the appropriation necessary to complete the transaction. Superintendent Peirce was asked to have a reconnaissance made of the coast of Alaska, and a compilation of the most reliable information obtainable concerning its natural resources. A party led by Assistant George Davidson sailed from San Francisco on 21 July 1867 and returned 18 November 1867. Davidson's report of 30 November was received by Superintendent Peirce in January, reached President Johnson early in February, and was a principal document in his message of 17 February to the House of Representatives, recommending the appropriation. The bill was finally enacted and signed by the President in July.

Charles's younger brother, Benjamin Mills Peirce, returned in the summer of 1867 from two years at the School of Mines in Paris. Seward wished to explore the possibility of purchasing Iceland and Greenland from Denmark. His expansionist supporter Robert J. Walker consulted Superintendent Peirce, who had his son Ben compile A Report on the Resources of Iceland and Greenland which he submitted on 14 December 1867, and which his father submitted to Seward on the 16th. With a foreword by Walker, it was published in book form next year by the Department of State. But congressional interest in acquiring the islands was insufficient and no action was taken. 1

Joseph Winlock had become the third Director of the Harvard College Observatory in 1866, and working relations between the Survey and the Observatory became closer than they had previously been. (Winlock had been associated with the American Ephemeris and Nautical Almanac from its beginning in 1852, and for the last several years had been its Superintendent, residing in Cambridge. Benjamin Peirce had been its Consulting Astronomer from the beginning. Charles had done some work for it in recent years. Assistant William Ferrel and he had observed the annular eclipse of the sun at St. Joseph, Missouri, 19 October 1865, and both had submitted written reports to Winlock which are still preserved.) By arrangement with Winlock, Charles began in 1867 to make observations at the Observatory that were reported in subsequent volumes of its Annals. In 1869 he was appointed an Assistant in the Observatory, where, as in the Survey, the rank of Assistant was next to that of Director.

In 1867 the Observatory received its first spectroscope. Among the most immediately interesting of the observations it made possible were those of the auroral light. In volume 8 of the Annals it was reported that "On April 15, 1869, the positions of seven bright lines were measured in the spectrum of the remarkable aurora seen that evening; the observer being Mr. C. S. Peirce."

By that time, Peirce had begun reviewing scientific, mathematical and philosophical books for the Nation. His second review was of Roscoe's Spectrum Analysis, on 22 July 1869, and it was both as chemist and as astronomer that he reviewed it. With Winlock's permission, he reported that

"In addition to the green line usually seen in the aurora, six others were discovered and measured at the Harvard College Observatory during the brilliant display of last spring, and four of these lines were seen again on another occasion. On the 29th of June last, a single narrow band of auroral light extended from east to west, clear over the heavens, at Cambridge, moving from north to south. This was found to have a continuous spectrum; while the fainter auroral light in the north showed the usual green line."2

Peirce was a contributor to the Atlantic Almanac for several years, beginning with the volume for 1868. In that for 1870 he had, among other things, an article on "The Spectroscope," the last paragraph of which was devoted to the spectrum of the aurora borealis and the newly discovered lines.

As an Assistant both in the Survey and in the Observatory, Peirce was an observer of two total eclipses of the sun, at Bardstown, Kentucky, 7 August 1869, and near Catania, Sicily, 22 December 1870. And as late as 1894 he would write: "Of all the phenomena of nature, a total solar eclipse is incomparably the most sublime. The greatest ocean storm is as nothing to it; and as for an annular eclipse, however close it may come to totality, it approaches a complete eclipse not half so near as a hurdy-gurdy a cathedral organ."

In 1871 the Observatory acquired a Zšllner astrophotometer and Winlock made Peirce responsible for planning its use. More of that in our next volume. And in 1871 Peirce’s father obtained authorization from Congress for a transcontinental geodetic survey along the 39th parallel, to connect the Atlantic and Pacific coastal surveys. This led to Charles's becoming a professional geodesist and metrologist; but that too is matter for the third and later volumes. Back now to 1867.