“If ever I undertook the supremely difficult inquiry of what was conducive to our welfare I should feel that I needed to arm myself beforehand with whatever resources logic could afford, to speak of no others.”

The Peirce Project is home to many resources, some uniquely significant, that are crucial for the study of the many facets of Peirce’s works. Access the descriptions of those resources by navigating the menu on the left. We also provide links to other valuable resources online (work in progress: other websites already provide an abundance of such links).

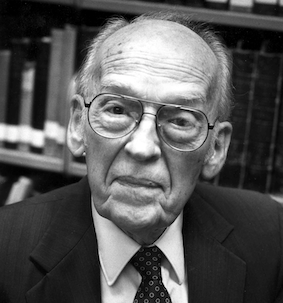

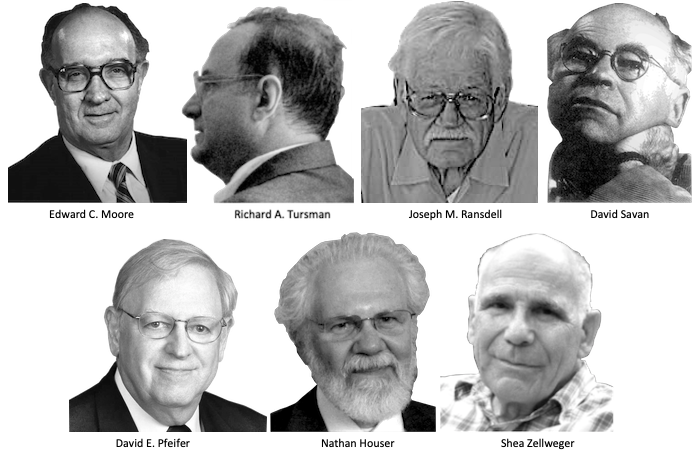

Max Harold Fisch* (1900–1995) is considered as the founding father of Peirce scholarship, and he is the founding general editor of the Peirce Edition Project. He spent the bulk of his long scholarly life studying Peirce—principally, but he had many other scholarly interests. In 1959 he was appointed official biographer of Charles S. Peirce by the Philosophy Department of Harvard University. That Department owns the Peirce Papers (preserved in the Houghton Library). Fisch was given unparalleled access to the Peirce papers for decades. Over the course of 50 years he accumulated an enormous amount of information regarding Charles S. Peirce, his relatives, his colleagues, his academic, scientific, social, intellectual, and historical universe. He maintained assiduous correspondence with hundreds of other researchers nationally and internationally, and visited or contacted many libraries and archives to track Peirce-related documents and obtain copies of them. When Max Fisch left IUPUI in 1991, he donated all of his papers and his stellar library to the Peirce Project, along with the collection that had been put under his care by a prestigious colleague of his: Charles W. Morris.

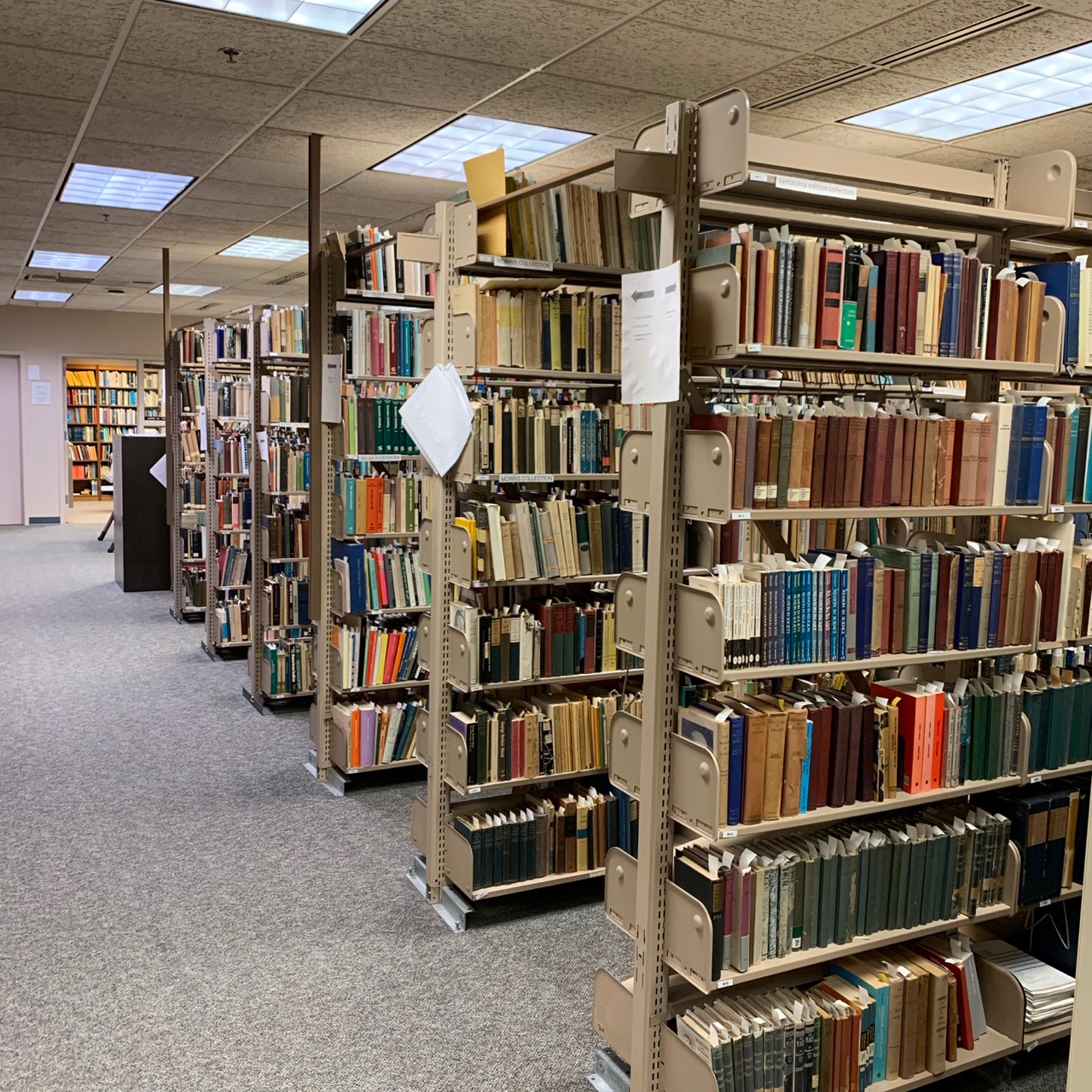

The “Max H. Fisch Library” was therefore initially created to name that most precious set of collections: his papers, his books, and the Morris books and papers (associated with the twentieth-century “Unity of Science Movement” that is a huge part of the origin of the spread of analytical philosophy in the United States). It was only after the Institute for American Thought was created, and after its components moved to the basement of the ES building, that the “Max H. Fisch Library” was extended, as a moniker meant to celebrate and honor Max Fisch’s memory, to other collections that were in time added to the library. What makes the Max H. Fisch Library unique among other things is its concentration on classical American philosophy as a whole within the much larger social, intellectual, economic, scientific, and historical context of the times. The late specialist of American philosophy, Peter H. Hare, declared that the IAT collections were to his knowledge the best in the world, more so than in any other research center of high respectability in classical American philosophy he had seen.

Essential to keep in mind is that the “Max H. Fisch Library” was reconceived in this manner to play a strategic goal within the Institute for American Thought, that of unifying all of its scholarly and research pursuit under the name of one of the most respected scholars and historians of philosophy in US history. Such a unification resulted from critical attention given to the specialized consolidation of library holdings. It mattered a great deal that all books be connected (1) to nineteenth-century to mid-twentieth-century intellectual history; (2) to Peirce’s vast realm of intellectual pursuits: mathematics and the history and philosophy of mathematics, science and the history and philosophy of science, philosophy and the history of philosophy, logic and the history of logic, semiotics; (3) to some of Max Fisch’s own realm of interests that made him famous, especially his work on Italian philosopher Vico, Gentile, and others, on top of his own research on stoic law and classical Greek philosophy; (4) pragmatism and the other great pragmatist philosophers (William James, John Dewey, Josiah Royce, and other Peirce contemporaries or followers); (5) the Unity of Science Movement (Morris); (6) past and contemporary secondary literature related to such topics.

Such a strategy has paid off in different ways. The library has become a principal reason that attracts national and international scholars, whether well established or doing graduate-level research, to visit the IAT and conduct short- or long-term research in our premises. Our library’s specialized concentration has in turn attracted additional donations from significant scholars looking for an ideal place as a repository for their own intellectual legacy.

In addition to comprehensive collections of books and periodicals relating to Peirce and Vico, the Max Fisch Library contains over 13,000 volumes in philosophy, the classics, literature, history, psychology, religious studies, sciences, and languages, many of which are out of print today. Fisch’s papers include a comprehensive biographical reference catalog that, along with the edition’s master reconstruction of Peirce’s known writings, draw research scholars from all over the world.

* See David L. Marshall’s paper, “Historical and Philosophical Stances: Max Harold Fisch, A Paradigm for Intellectual Historians,” in European Journal of Pragmatism and American Philosophy 8.2 (2009): 248–74 for a presentation of Fisch’s scholarly acumen.

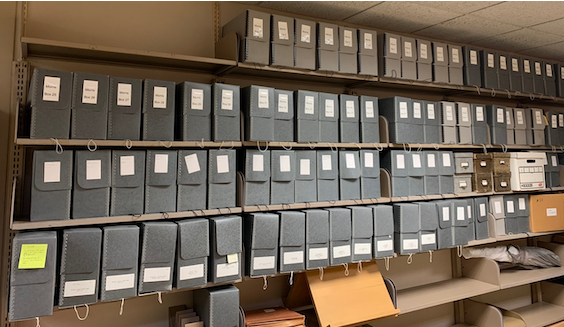

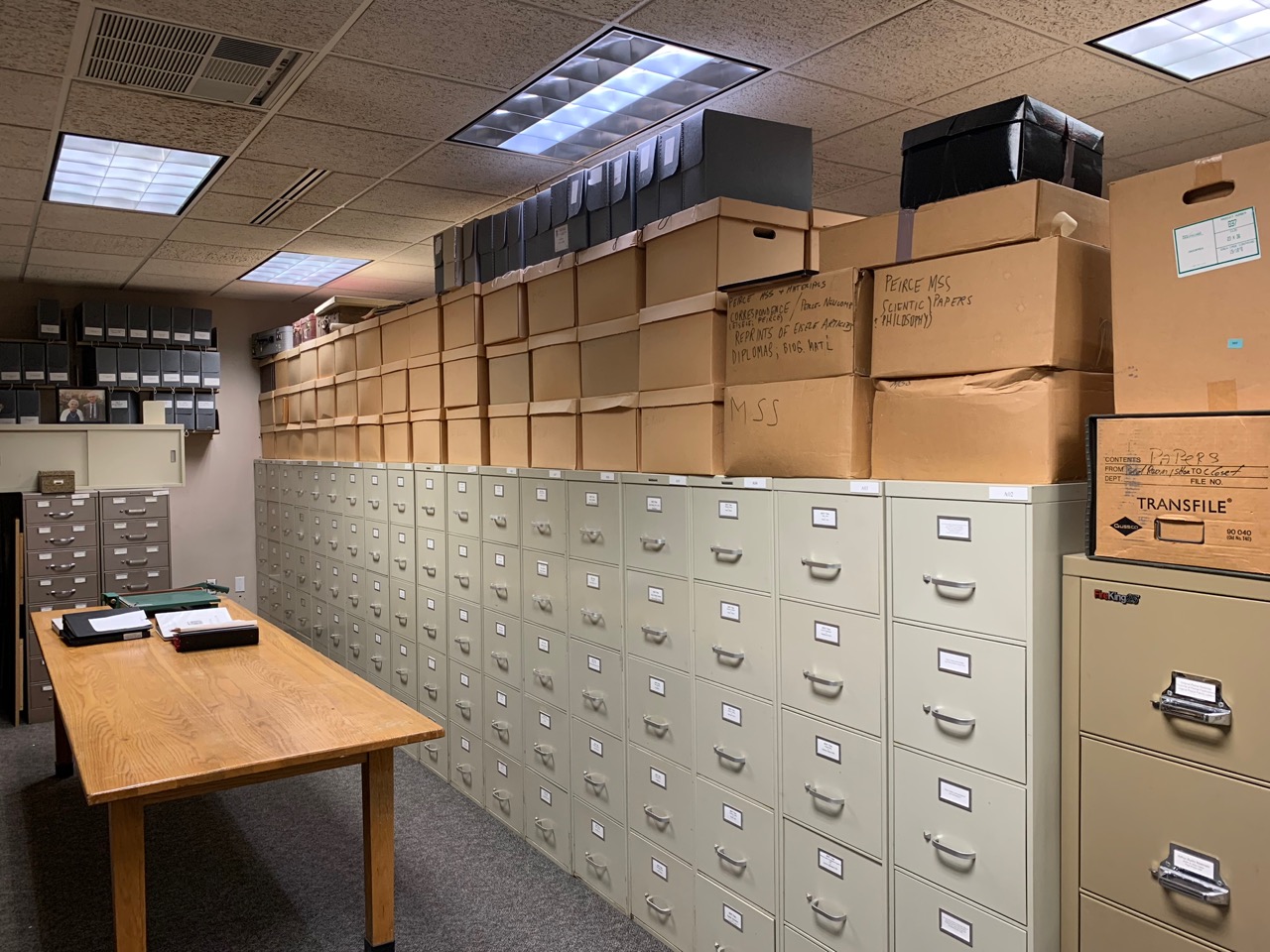

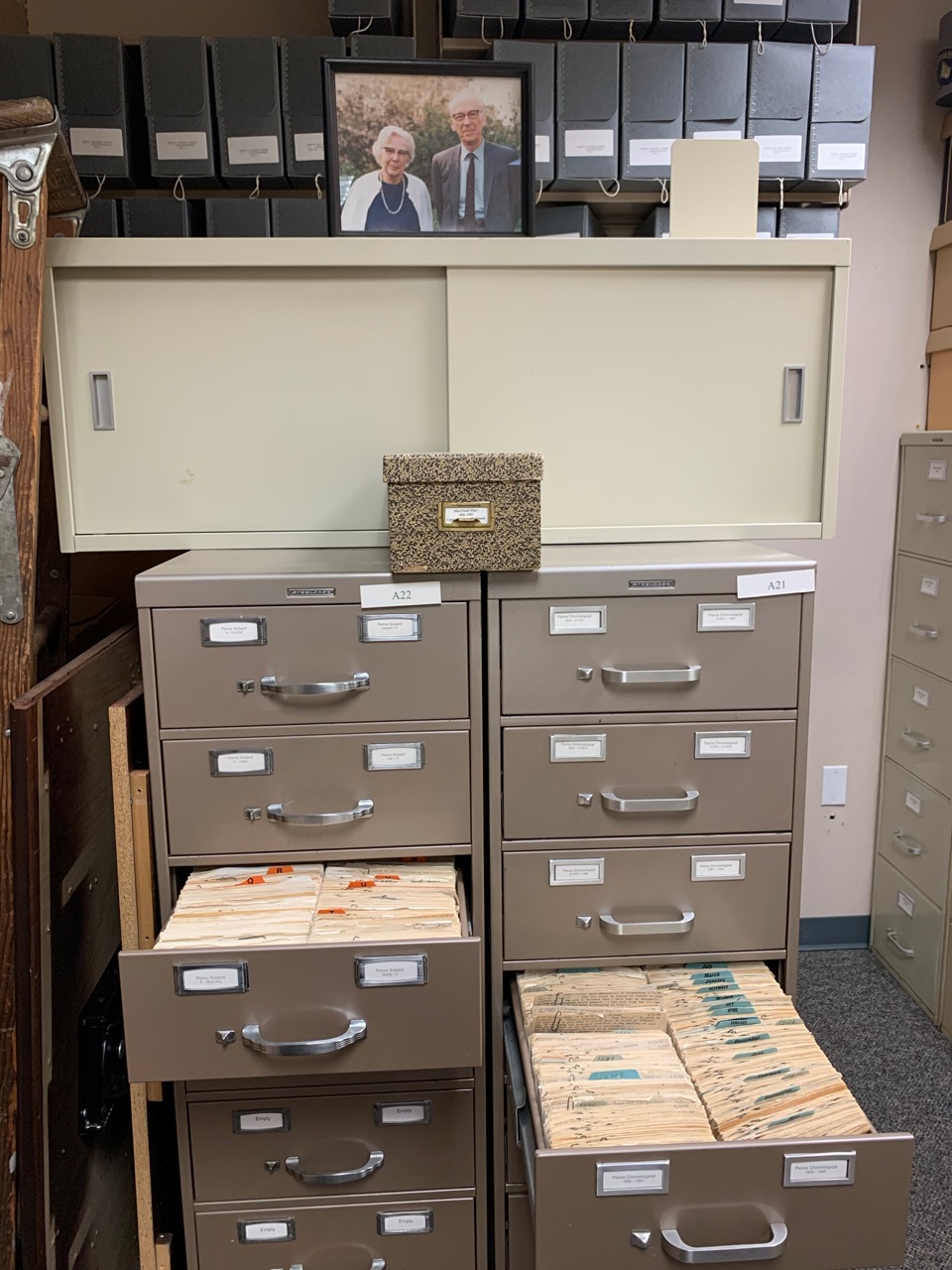

The Max H. Fisch Papers occupy 65 drawers which include correspondence, lectures, notes, published articles, pamphlets, conference programs, newspaper clippings, and other items connected with his research. The main finding aid is downloadable here, and the supplement finding aid here.

Useful to know is that the University of Illinois Archives own a collection titled “Max Fisch Papers, 1928–67” consisting of ten boxes of papers arranged by subject; here is a link to its finding aid (downloadable PDF). Two other collections at the University of Illinois Archives also contain substantial Fisch-related documents: the D. Walter Gotshalk Papers, 1925, 1927-1970 and the Jordan, Elijah. Papers, 1899-1962.

The Max H. Fisch Collection includes numerous books (560 linear feet) catalogued in an Endnote database downloadable here. Many of these books are now out of print. Fisch’s books range in topics and include philosophy (classical, medieval, modern, and contemporary), the classics, literature, history, psychology, religious studies, science, languages, Charles S. Peirce, and Giambattista Vico.

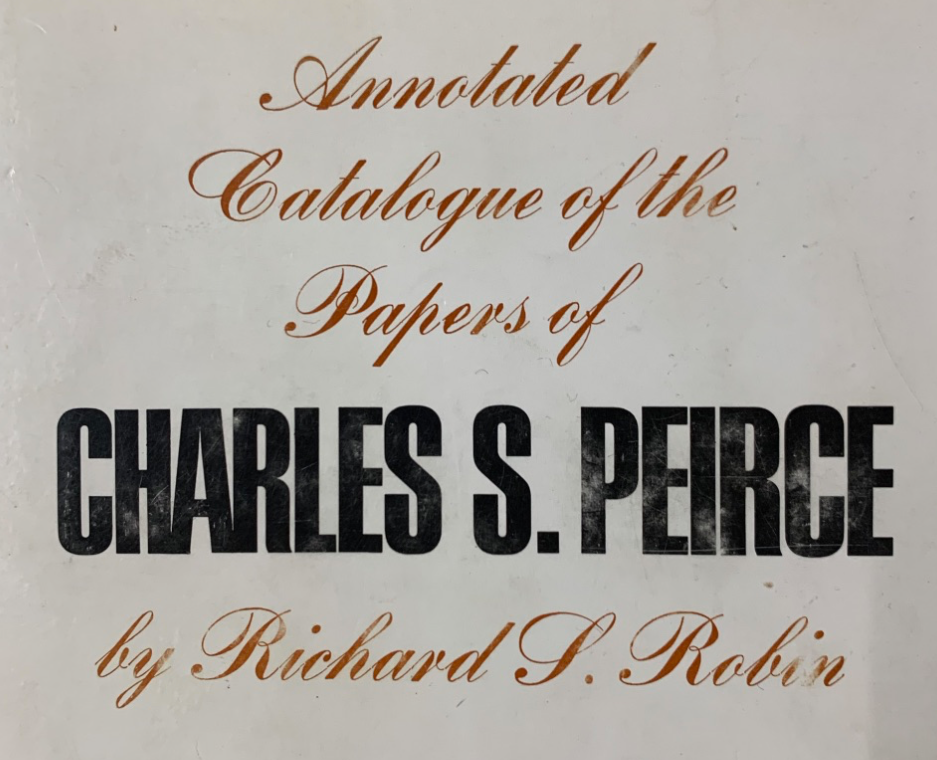

During his forty years of researching Charles S. Peirce, Max H. Fisch compiled a comprehensive Reference Catalog, which is part of the Max H. Fisch Collection. The Reference Catalog (about 60,000 3" X 5" slips) is divided by subject, chronological year, and manuscript number in accordance with the Robin Catalog. The Reference Catalog contains Peirce quotes and information about his writings, professional dealings, colleagues, family, and personal life.

The Max H. Fisch Library is a large and complex cluster of scholarly resources and collections, the vast majority of which is associated with the Peirce Edition Project. Administratively, the Max H. Fisch Library depends on the Institute for American Thought and is sometimes informally called the IAT Library.

Here is a link to a PDF that describes the collections and resources associated with the Peirce Edition Project. They are divided into three categories: those that constitute the Max H. Fisch Library (related to the research operation of the Peirce Project): pp. 1–17; those that are related to the editorial operation of the Peirce Project: pp. 18–20 (here is an old finding aid); and those that are related to the art of the theory, practice, and teaching of critical textual editing: pp. 20–21. An online catalog of the books in some of the collections of the Max H. Fisch Library is accessible at this URL (not those of the Max Fisch Collection itself, which were catalogued separately in an Endnote database downloadable here).

THE MAJOR COLLECTIONS INCLUDE:

* Books of Paul Weiss that contain annotations in his hand are held separately in IU Indianapolis Library’s Special Collections: see their inventory in this downloadable PDF.

THE SMALLER COLLECTIONS INCLUDE:

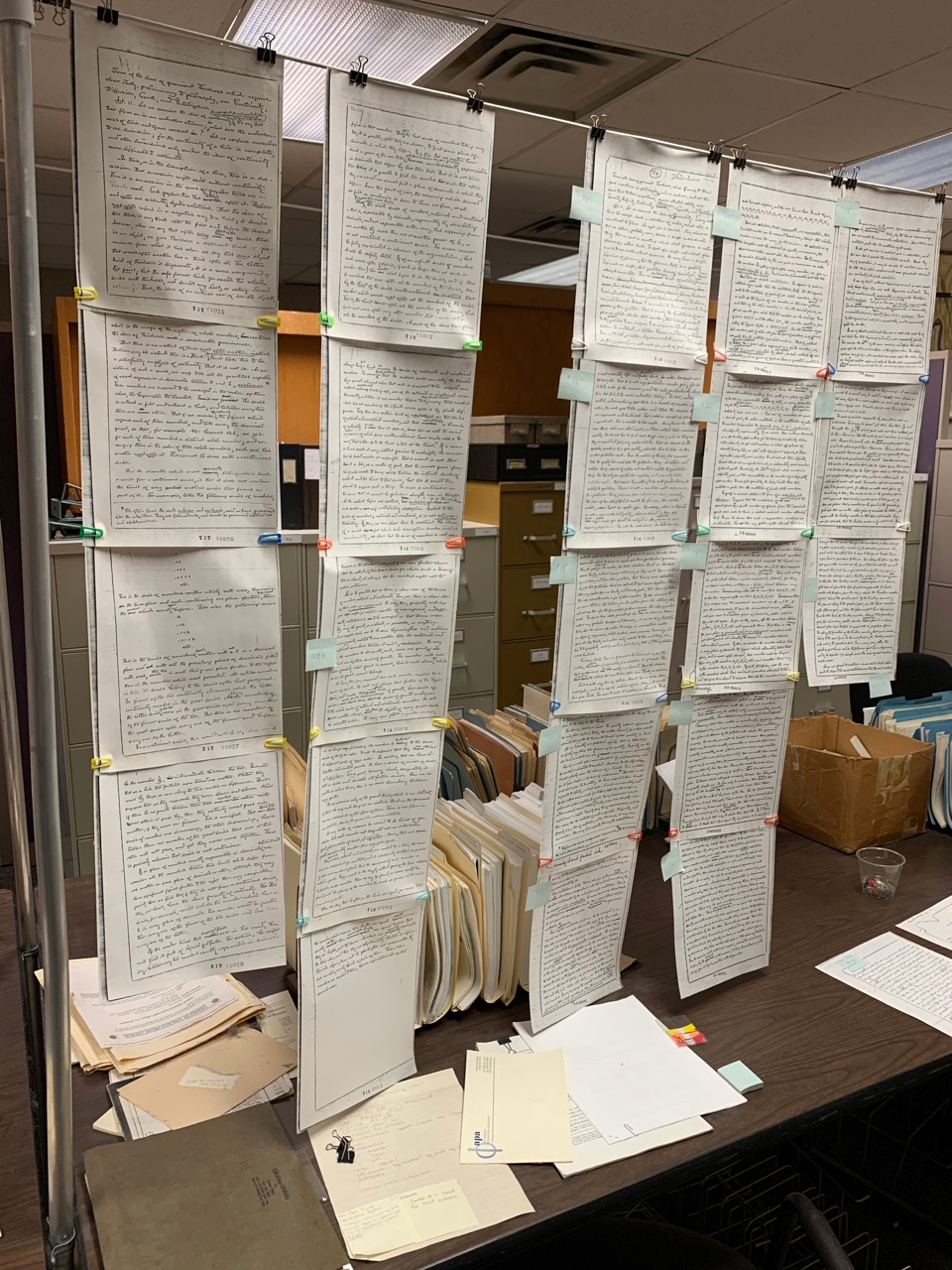

THE ARCHIVES GENERATED BY THE PEIRCE PROJECT’s decades of operation have naturally grown as work on our volumes proceeds at a speed that varies according to funding and staffing. PEP-related Collections include artifacts and many drawers full of folders. Those myriad folders include:

Artifacts include objects and display received on permanent loan from NOAA (which includes the US Coast and Geodetic Survey, the government entity Peirce worked for over 31 years).

PEP collection also includes copies of numerous doctoral dissertations and master’s theses; a complete set of the annual reports of the US Coast and Geodetic Survey; several copies of the Century Dictionary and Cyclopedia (of which Peirce was a principal contributor) as well as a full copy of Peirce’s own interleaved set of that dictionary’s first printing, replete with his supplementary entries.

Digitized copies of select Peirce manuscripts have been uploaded online in multiple locations. Here are a few links to the major online repositories.

The Institute for Studies in Pragmaticism is the first and thus oldest organized research center on Peirce. Two prominent Peirce scholars created it in 1972 at Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas. They were Charles S. Hardwick and Kenneth L. Ketner, who brought in Max H. Fisch as a visiting professor in their university. The Institute became the strategic and conceptual birthplace of what was to become the Peirce Edition Project in Indianapolis. The mission of the Institute was and remains to this day to facilitate study of the life and works of Peirce and his continuing influence within interdisciplinary sciences. As of spring 2020, the Institute has a new director, Charles Sanders Peirce Interdisciplinary Professor Elize Bisanz.

Among the major resources produced by the Institute is A Comprehensive Bibliography of the Published Works of Charles Sanders Peirce with a Bibliography of Secondary Studies, under the joint editorship of Kenneth L. Ketner, Christian J. W. Kloesel, Joseph M. Ransdell, Max H. Fisch, and Charles S. Hardwick (Greenwich, CT: Johnson Associates, 1977). Professor Ketner published a second revised edition in 1986 under the aegis of the Philosophy Documentation Center.

That bibliography incorporated all previous bibliographies (eight of them, compiled between 1916 and 1974 by Morris Cohen, Irving C. Smith, Daniel C. Haskell, Arthur W. Burks, and especially Max H. Fisch, who compiled half of them). It served as a companion to another major product: a collection of 149 microfiches titled Charles Sanders Peirce: Complete Published Works, included Selected Secondary Materials (Greenwich, CT: Johnson Associates, 1977). This collection was subsequently made available by the Philosophy Documentation Center under the title Charles S. Peirce Microfiche Collection. It was completed in 1986 by 12 supplementary microfiches.

In 2013, that entire collection was digitized and ported online, where it can be viewed through 1248 downloadable PDFs. That set of PDFs constitute the Third Digital Edition of The Published Works of Charles Sanders Peirce. Explanations regarding its method of preparation, how to use it, and how to refer to it in the form of a bibliographical citation, are provided in an online guide. The digitized version of the Comprehensive Bibliography consists of a PDF document that is also downloadable.

For the convenience of researchers, we provide below an alternate tabulation of the PDF links, organized by publication year.

P numbers denote publications by Peirce;

O numbers publications by authors other than Peirce.

Each link displays the title of the publication and its source as found in the Comprehensive Bibliography, including a number of revisions or corrections based on Peirce Project findings. Missing P or O numbers (principally O numbers) denote by their absence documents that were not filmed in the microfiche edition; they are marked “(NF)” in the Comprehensive Bibliography.

Boston Daily Evening Traveller (4 August), page 4, columns 5–6.

Boston Daily Evening Traveller (5 August), page 1, columns 6–7.

Boston Daily Evening Traveller (9 August), page 4, columns 5–6.

Boston Daily Evening Traveller (10 August), page 2, columns 4–5.

Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 1859, House Ex. Doc. No. 41, 36th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Thomas H. Ford, p. 36.

Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 1860, House Ex. Doc. No. 14, 36th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 85–86.

The American Journal of Science and Arts, second series 35, whole series 85 (January 1863), 78–82. The article is dated, “Cambridge, Mass., Dec. 1862.”

Oration delivered at the reunion of the Cambridge High School Association, Thursday evening, 12 November. Extracts printed in Cambridge Chronicle, 18 (21 November), no. 47, page 1, columns 1–5. See R 1638.

The North American Review, vol. 98 (April), 342–369. The page heading of this review is “Shakespearean Pronunciation.” Written in collaboration with John Buttrick Noyes.

Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 1862, House Ex. Doc. No. 22, 37th Congress, 3d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 15–16, 155–156, 157–158.

Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 1863, House Ex. Doc. No. 11, 38th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 146– 154; See also p. 15.

Privately printed booklet. “Distributed at the Lowell Institute, Nov., 1866, by Charles S. Peirce, of Cambridge, Mass.”

Report of the Superintendent of the Coast Survey, 1864, House Ex. Doc. No. 15, 38th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 114; see also p. 11.

The North American Review, vol. 105 (July), 317–321.

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 2, 57–61. The article refers to a previous work in the same journal at 1 (1867), 250–256—those pages are filmed here to facilitate understanding of the issues Peirce and Harris are discussing in P 00025.

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 2, 103–114.

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 2, 140–157.

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 2, 191–192. See P 00025 and P 00028.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 7, 250–261. Read before the Academy on 12 March 1867.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 7, 261–287. Read before the Academy on 9 April 1867.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 7, 287–298. Read before the Academy on 14 May 1867.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 7, 402–412. Read before the Academy on 10 September 1867.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 7, 416–432. Read before the Academy on 13 November 1867.

The American Journal of Science and Arts, second series 48, whole series 98 (November), 404–405.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1869, Boston: Ticknor and Fields, pp. 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1869, Boston: Ticknor and Fields, pp. 62–64.

Chemical News, American Supplement. American reprint vol. 4 (June), 339–340. Letter to the editor.

The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, vol. 2, 193–208.

The Nation, vol. 9 (22 July) 73–74, filmed at P 00043, pages 29–32.

The Nation, vol. 9 (25 November) 461–462, filmed at P 00043, pages 32–37.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1866, House Ex. Doc. No. 87, 39th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 24–25; see also p. 22 for mention of the “Schooner Peirce.”

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1867, House Ex. Doc. No. 275, 40th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 19.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1861, House Ex. Doc. No. 275, 40th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 19–20, filmed at P 00047.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1870, Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., p. 61.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1870, Boston: Fields, Osgood & Co., pp. 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46.

The Nation, vol. 11 (4 August) 77–78, filmed at P 00043, pages 38–40. Probably by Peirce.

The North American Review, vol. 110 (April), 463–468.

The Nation, vol. 12 (20 April) 276, filmed at P 00043, pages 41–42. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 13 (30 November) 355–356; see also vol. 13 (2 November 1871) 294, filmed at P 00043, pages 43–45.

The Nation, vol. 13 (14 December), 386, filmed at P 00043, page 45. Signed letter.

The North American Review, vol. 113 (October), 449–472.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 16 December. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 35. Announcement only.

Report of the Fortieth Meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science, held at Liverpool in September 1810, second sequence of pages, pp. 14–15. See P 00052.

Paper read before the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 12 March. Cited in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 8 (May 1868 to May 1873), Boston and Cambridge: Welch, Bigelow, and Company, 1873, p. 412.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1812, Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, pp. 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46.

The Nation, vol. 14 (11 April) 244–246; see also 14 (4 April 1872) 222. Peirce definitely wrote the review of Wilson’s book, and probably also wrote the reviews of the other books mentioned in this review article. Filmed at P 00043, pages 46–51.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 19 October. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 63. See MSS 1055 and 1059. Announcement only.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 21 December. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 68, abstract given. See R 1131. Announcement only.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1869, House Ex. Doc. No. 206, 41st Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 38–39.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1873, Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, pp. 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46.

The Nation, vol. 17 (10 July) 28–29, filmed at P 00043, pages 52–54.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 17 May. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 88. Announcement only.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1870, House Ex. Doc. No. 112, 41st Congress, 3d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 229–232.

The Atlantic Almanac, 1874, Boston: James R. Osgood and Company, pp. 2, 6, 10, 14, 18, 22, 26, 30, 34, 38, 42, and 46.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 14 March. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 94. See also pp. 39 and 48 for Peirce’s appearance on membership list and contributor’s list. Announcement only.

Paper read before the Philosophical Society of Washington, Washington, D.C., 14 March. Cited in Bulletin of the Philosophical Society of Washington, vol. 1 (1874), 97. Announcement only.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1871, House Ex. Doc. No. 121, 42d Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 9–14. Charles is mentioned at pp. 10 and 11.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1871, House Ex. Doc. No. 121, 42d Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 180–184. Peirce is mentioned at p. 182.

Paper read before the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 9 March. Cited in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 2, whole series 10 (May 1874 to May 1875), Boston: Press of John Wilson and Son, 1875, p. 473.

Annual Record of Science and Industry for 1874, edited by Spencer F. Baird, New York: Harper and Brothers, pp. 324–325. Abstract of Peirce’s article “On the Theory of Errors of Observation.”

The Democratic Party, by Melusina Fay Peirce, Cambridge: John Wilson and Son, pp. 36–37.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1872, House Ex. Doc. No. 240, 42d Congress, 3d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 50–51.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1873, House Ex. Doc. No. 133, 43d Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 175–180.

Paper read before the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 11 October. Cited in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 4, whole series 12 (May 1876 to May 1877), Boston: Press of Wilson and Son, 1877, p. 283.

Mind, vol. 1 (July), 424–425; includes editor’s reply on p. 425.

The American Journal of Science and Arts, third series 13, whole series 113 (January to June), 247–251.

Annual Record of Science and Industry for 1876, edited by Spencer F. Baird, New York: Harper and Brothers, pp. 47–48. Abstract of the star catalogue prepared under Peirce’s supervision including the list of errata in the catalogue of Heis.

par Mr. Peirce du Coast Survey U.S.A. Note Communiquée par Mr. E. Plantamour. Association géodésique internationale. This is a lithograph distributed in advance of the Geodesic Conference.

The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, fifth series, 3 (supplement), 543–547. Reprint of P 00100.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 4, whole series 12 (from May, 1876 to May, 1877), Boston: Press of John Wilson and Son, pp. 289–291.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1814, House Ex. Doc. No. 100, 43d Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 17–18.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 1, 59–63.

Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 2, p. 661; see also p. 574. Abstracted into German by G. Wiedemann from Peirce’s article in Nature, vol. 18 (1878), 381.

The Nation, vol. 27 (1 August) 74, filmed at P 00043, page 55.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, New York City, 5–8 November. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1883, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 85, 48th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1884, Appendix D, p. 49.

Nature, vol. 18 (4 July), 258–260. Conversation with Peirce mentioned at 260.

Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, vol. 9, Leipzig: Wilhelm Engelmann.

The Popular Science Monthly, vol. 12 (January), 286–302.

The Popular Science Monthly, vol. 12 (March), 604–615.

The Popular Science Monthly, vol. 13 (August), 470–482.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 5, whole series 13, 115– 116; see also 427–428. Read before the Academy on 10 October 1877.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 5, whole series 13 (May 1877 to May 1878), pp. 396–401; see also p. 433. Presented by title before the Academy on 13 March. See P 00253.

“Pendulum observations, “ in Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1875, House Ex. Doc. No. 81, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 19.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1875, House Ex. Doc. No. 81, 44th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 249–253.

Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Etranger, vol. 6 (December), 553–569.

Verhandlungen der vom 27 September bis 2 October 1877 zu Stuttgart abgehalten fünften allgemeinen Conferenz der Europaischen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 4, 20, 23, 100–104, 118, and 139.

Verhandlungen der vom 27 September bis 2 October 1877 zu Stuttgart abgehalten fünften allgemeinen Conferenz der Europaischen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 171–187. Comments on Peirce’s paper by Th. von Oppolzer are at pp. 188–192. Additional comments on Peirce by E. Plantamour are in an appendix entitled “Recherches Expérimentales sur le Mouvement Simultané d’un Pendule et de ses Supports.” pp. 3–5.

Paper read before the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, Boston, 11 June. Cited in Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 7, whole series 15, 369–370. See R 1072–R 1075.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 2, 330–347.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 2, 394–396, plus map plate. Erratum, American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 3 (1880). See P 00183.

The American Journal of Science and Arts, third series 18, whole series 118 (July), 51. See R 1072-R 1075.

The American Journal of Science and Arts, third series 18, whole series 118 (August), 112–119.

New York: Harper and Brothers, p. 111. Reference to Peirce’s participation in the fifth General Conference of the European International Geodetic Conference.

Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, vol. 89, 462–463.

Read before a meeting of the Metaphysical Club, Johns Hopkins University, on 28 October. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 18. Abstract given.

The Nation, vol. 28 (3 April) 234–235, filmed at P 00043, pages 56–58.

The Nation, vol. 29 (16 October) 260, fiImed at P 00043, pages 58–6–1. The last two paragraphs are not by Peirce, their author being Russell Sturgis.

The Nation, vol. 29 (25 December) 440, filmed at P 00043, pages 61–62.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1816, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 37, 44th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 6–9.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1876, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 37, 44th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 83–129. “The list was selected under the direction of Assistant C. S. Peirce...” (p. 83).

Science News, vol. 1 (1 May), pp. 196–198. See also pp. 193–198. Abstracts of the two papers Peirce presented at the meeting of the National Academy of Sciences, 15–18 April 1879 [“On Ghosts in Diffraction Spectra” and “Comparison of Wave Lengths with the Metre”]. Reprinted in Nature, 20, (29 May 1879), 99–101 with abridgements.

Verhandlungen der vom 4 bis 8 September 1878 in Hamburg Vereinigten Permanenten Commission der Europaischen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 8–9.

Verhandlungen der vom 4 bis 8 September 1878 in Hamburg Vereinigten Permanenten Commission der Europa7schen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 116–120.

American Journal of Science, third series 20, whole series 120 (October), 327. Reprinted in The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, fifth series 10 (November 1880), 387; see P 00174.

Beiblättter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 4, p. 240; see also bibliographic references to Peirce at pp. 78, 494, 572, 582, 695, and 846. Abstracted into German by

Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 4, p. 278. Abstracted into German by E. Wiedemann from Peirce’s article in Nature, vol. 21 (1879), 108.

Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, vol. 90 (June), 1401–1403.

Comptes Rendus des Séances de l’Académie des Sciences, vol. 90, 1463–1466. Review of “Sur la valeur de la pesanteur à Paris” by Charles Sanders Peirce.

The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, fifth series 10 (November), 387.

Given before the Metaphysical Club, Johns Hopkins University, on 13 January. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 34. Abstract of Marquand’s paper given.

Paper read before the Metaphysical Club, Johns Hopkins University, on 9 March. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 49. Abstract given.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1877, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 12, 45th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 17–18.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast Survey, 1877, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 12, 45th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 191–192. Same as American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 2 (1879), 394–396 plus map plate. Also reprinted in A Treatise on Projections, by Thomas Craig, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1882, p. 132.

Verhandlungen der vom 16 bis 20 September 1879 in Gent vereinigten Permanenten Commission der Europaischen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 7–10, 19–29.

Vierteljahresschrift der Astron. Gesellschaft, vol. 15, 193–208.

Paper read before the American Association for the Advancement of Science Cincinnati Ohio, August. Cited in Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Thirtieth Meeting, held at Cincinnati, Ohio, August, 1881, Salem: 1882, abstract given (presumably by Peirce) on p. 20. Notice of Peirce’s election to membership in the

Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 5, p. 12. Abstracted into German by E. Wiedemann from Peirce’s 1880 article in the American Journal of Science and Arts, vol. 20, p. 327.

Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 5, pp. 48–50. Abstracted into German by E. Wiedemann from Peirce’s 1879 article in the American Journal of Mathematics, vol.

Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie, vol. 5, p. 665. Abstracted into German by E. Wiedemann from Peirce’s 1881 article in Nature, vol. 24, p. 262.

Given before the Metaphysical Club, Johns Hopkins University, November. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 177.

The Nation, vol. 32 (31 March) 227, filmed at P 00043, pages 63–64.

Nature, vol. 23 (24 March), 485–487.

Proceedings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, new series 8, whole series 16 (24 May), 443–454. Obituary notice.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1878, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 13, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 4, 18.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1879, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 17, 46th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 27–29. Most of this article consists of quotations from Peirce about work in progress or published in other journals.

Revue Philosophique de la France et de l’Etranger, vol. 12, 646–650.

Paper read before the Scientific Association, Johns Hopkins University, February. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 128. Abstract given.

Verhandlungen der vom 13 bis 16 September 1880 zu Munchen Abgehaltenen Sechsten Allgemeinen Conferenz der Europaischen Gradmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 30–32; repeated on pp. 84–86.

Verhandlungen der vom 13 bis 16 September 1880 zu Munchen Abgehaltenen Sechsten Allgemeinen Conferenz der Europaischen Gradmessung. Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, pp. 43, 96, A ppendix II (pp. 1–12), Appendix IIa (pp. 1–8).

Privately printed brochure, Baltimore: 7 January; with a postscript dated 16 January.

Printed in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 184.

Paper read before the Mathematical Seminary, Johns Hopkins University, January. Cited in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 1 (1882), 179. Abstract given.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1880, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 12, 46th Congress, 3d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 19–20.

A Treatise on Projections, by Thomas Craig, Treasury Department, Document No. 61, Coast and Geodetic Survey, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 132, 247. This is extracted from Peirce’s report on this topic in the Coast Survey Report for 1877.

The American Journal of Science, third series 26, whole series 126 (October), 299–302.

Cronica Cientifica (Barcelona), vol. 6 (25 October), 447–449.

Printed in The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, voI. 2 (1883), 34.

The Johns Hopkins University Circulars, vol. 2, 86–88. See the related note by Sylvester printed immediately above Peirce’s “Communication.”

Mind, vol. 8, 594–603.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1881, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 26.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1881, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 359–441. See P 00126.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1881, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 442–456.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1881, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 457–460.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1881, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 461–463.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 4.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 19.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 32–33.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 503–516. Peirce is mentioned a few times in the report, and his recorded remarks are given at several points.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 506–508; filmed at P 00260.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882,

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 557. “Owing to the already bulky proportions of this volume, Appendix No. 23 [this title] has been transferred to, and wiII appear in, the Annual Report of the Superintendent for the year 1883.” Probably the article in the Report for 1883 that is the successor of this unprinted piece is “Determinations of Gravity at Allegheny, Ebensburgh, and York, Pa., in 1879 and 1880.”

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1882, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 77, 47th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 559–563; Peirce’s comments are at p. 563.

Edited by C. S. Peirce, Boston: Little, Brown, and Company. The following parts of the book are by Peirce: “Preface” iii-vi; “A Theory of Probable Inference” 126–181; “Note A (On a Limited Universe of Marks)” 182–186; “Note B (The Logic of Relatives)” 187–203.

American Academy of Arts and Sciences, vol. 19, 477–483, at 483.

A discussion of pendulum experiments and weights and measures given before the American Metrological Society meeting at Columbia College in New York City, 30 December. Cited (with summary account of the discussion) in Proceedings of the American Metrological Society, from May, 1884, to December, 1885, New York: Published by the Society, 1885, pp. 46–48, 83.

Mind, vol. 9, 93–109, at 107–108.

The Nation, vol. 39 (18 December) 521, filmed at P 00043, pages 65–66. Signed letter, with editor’s reply.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, Newport, 14–17 October. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1884, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 68, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1885, p. 12.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, Newport, 14–17 October. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1884, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 68, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1885, p. 12; filmed at P 00281. See P 00303 for the paper as published.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, Newport, 14–17 October. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1884, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 68, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1885, p. 13; filmed at P 00281.

Proceedings of the London Mathematical Society, vol. 15 (3 April) 185–197, at 186–187, 194–197.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1883, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 29, 48th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 27.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1883, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 29, 48th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 36–37; see also pp. 96–97.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1883, Senate Ex. Doc. No. 29, 48th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 41–42.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 7 (January), 180–202.

Lecture given before the Association of Engineers, Cornell University, Friday, 4 December. Cited in The Cornell Daily Sun, Ithaca, New York (Thursday, 3 December), p. 1. Filmed at P 00302.

The Evening Post, New York City, vol. 84 (Friday, 10 August), page 3, column 3.

Jahrbuch über die Fortschritte der Mathematik, Jahrgang 1882, vol. 14, part 2, pp. 594–595.

Lecture given before the Mathematical Seminary, Cornell University, Tuesday, 1 December. Cited in The Cornell Daily Sun, Ithaca, New York, Monday, 30 November and Thursday, 3 December.

Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences, 1884, Washington: Government Printing Office, 73–83. Read before the Academy on 17 October 1884 under the title, “On Minimum Differences of Sensibility.” For paper read, see P 00282.

The Nation, vol. 40 (1 January) 12, filmed at P 00043, page 67. Signed letter.

The Nation, vol. 41 (3 September) 203, filmed at P 00043, pages 68–69. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 41 (19 November) 431, filmed at P 00043, pages 69–70.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 6–7; see also a reference to these pages (which identifies this as an account of Peirce’s work) at pp. 80–81. Compare a similar brief reference at p. 2; pp. 80–81 filmed at P 00312.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 40.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 80–81.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 87–93; Peirce is mentioned at p. 89 and p. 93.

by Edwin Smith, Assistant.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 475–482.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1884, House Ex. Doc. No. 43, 48th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 483–485.

Science, vol. 6 (21 August), 158. The letter is dated “Ann Arbor, Mich., Aug. 10.”

The Washington Post (Saturday, 25 July),.page 1, column 7.

The Washington Post (Sunday, 26 July), page 2, column 1.

The Washington Post (Monday, 3 August), page 1, column 7.

The Washington Post (Thursday, 6 August), page 1, column 7.

The Washington Post (Wednesday, 12 August), page 1, column 7.

Cited in Cornell Daily Sun, Ithaca, New York, vol. 6 (5 February), page 1, columns 1–2.

The Nation, vol. 42 (11 February) 135–136, filmed at P 00043, pages 71–74.

Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Thirty-fourth Meeting Held at Ann Arbor, Mich., August, 1885, Salem: Published by the Permanent Secretary, pp. 545–546, minutes for the executive meeting of Friday Morning, August 28, 1885.

“Gravity determinations and experimental researches at Washington, D.C., and in Virginia.”

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1885, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 81–86; Peirce is mentioned at p. 83 and p. 84; compare p. 99.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1885, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 503–508.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1885, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 509–510.

Science, vol. 8 (22 October), 359–360.

Testimony before the Joint Commission [etc.], Senate Mis. Doc. No. 82, 49th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 370–378; see also pp. 839, 852. Peirce’s testimony was presented on 24 January 1885.

New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, vol. 1, pp. 67–68, 124–133, 135– 136, 178–180.

The Washington Post (Sunday, 17 October), page 2, column 2.

The Washington Post (Monday, 18 October), page 2, column 6.

American Journal of Psychology, vol. 1 (November), 112–127, at 116, 118, 121n, 125–126.

The American Journal of Science, third series 33, whole series 133, 167–182, at 175, 181, 182.

In Science and Immortality; the Christian Register Symposium, Revised and Enlarged, Edited and Reviewed by Samuel J. Barrows, Boston: Geo. H. Ellis, pp. 69–76; comments on Peirce’s contribution are at pp. 109–111; a brief biographical statement on Peirce is at p. 135.

The London, Edinburgh, and Dublin Philosophical Magazine and Journal of Science, fifth series, vol. 24, 463–466, at 463.

Proceedings of the American Society for Phychical Research, old series vol. 1 (December), 150–157.

Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research, old series vol. 1 (December), 157–179.

Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research, old series vol. 1 (December), 180–215.

Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, vol. 42, 193–196.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1886, House Ex. Doc. No. 40, 49th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 41; see also p. 12.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1886, House Ex. Doc. No. 40, 49th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 49.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1886, House Ex. Doc. No. 40, 49th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 85–86.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1886, House Ex. Doc. No. 40, 49th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 97–103, see pp. 99, 100, 103.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1886, House Ex. Doc. No. 40, 49th Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 134–137, see pp. 135, 137.

The American Journal of Science, third series 35, whole series 135, 265–282 plus 347–367.

The American Journal of Science, third series 35, whole series 135, 337–338.

Treasury Department, Document no. 1089. Director of the Mint.

Report on the Proceedings of the United States Expedition to Lady Franklin Bay, Grinnell Land, by Adolphus W. Greely, House Misc. Doc. 393, Part 2, 49th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 701–714; see also comments by Greely at p. 715 plus comments and tables by Henry Farquhar at pp. 716–729. Includes Index, pp. 735–736.

Verhandlungen der vom 21 bis zum 29 October 1887 auf der Sternwarte zu Nizza abgehalten Conferenz der Permanenten Commission der lnternationalen Erdmessung, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer; Neuchatel: lmprimé par Attinger Frères, pp. 3–7. 15–16, Appendix IIa (pp. 1–7, 15–16, and Table IV), Appendix llf (pp. 1–3, 15–17, and Table IV).

Meteorological Observations made during the years 1840 to 1888 inclusive, Annals of the Astronomical Observatory of Harvard College, vol. 19, part 1: 50, 66–70, 78–81.

The Nation, vol. 48 (13 June) 488, filmed at P 00043 page 75. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 48 (20 June) 504– 505, filmed at P 00043 pages 75–78. Signed letter.

The Nation, vol. 48 (27 June) 524, filmed at P 00043, pages 77–78. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 49 (15 August) 136–137, filmed at P 00043, pages 78–80. Probably by Peirce.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, Washington, 16–19 April. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1889, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 47, 51st Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891, p. 6. Notice of research grants to Peirce are given at p. 38.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, Washington, 16–19 April. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1889, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 47, 51st Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1891, p. 6; filmed at P 00379.

Proceedings of the American Society for Psychical Research, old series 4 (March), 286–301.

Report of the Superintendent of the United States Coast and Geodetic Survey, 1887, House Ex. Doc. No. 17, 50th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, references to Peirce’s research at p. 116–117, 88.

The Monist, vol. 1 (October), 148–156, at 155. Mention that Peirce’s logic is taught in an advanced course instructed by Jastrow.

The Nation, vol. 50 (27 February) 184, filmed at P 00043, pages 81–82.

The Nation, vol. 50 (27 March) 265, filmed at P 00043, page 82.

The Nation, vol. 50 (19 June) 492–493, filmed at P 00043, pages 83–86.

The Nation, vol. 51 (3 July) 16, filmed at P 00043, pages 86–88.

The Nation, vol. 51 (7 August) 118–119, filmed at P 00043, pages 88–89.

The Nation, vol. 51 (28 August) 177, filmed at P 00043, page 90.

The Nation, vol. 51 (18 September) 234, filmed at P 00043, pages 91–93. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 51 (25 September) 254–255, filmed at P 00043, pages 93–96.

The Nation, vol. 51 (23 October) 326, filmed at P 00043, pages 96–97. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 51 (30 October) 349, filmed at P 00043, pages 97–98.

New York Daily Tribune (Friday, 8 Dec., 1890), page 10, column 2.

New York Daily Tribune (Tuesday, 19 Dec., 1890), page 16, columns 5–6.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 23 March), page 4, column 4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 23 March), page 4, columns 6–7. Signed “Outsider.”

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 30 March), page 4, column 4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 30 March), page 13, column 1.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 30 March), page 13, columns 1–2.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 30 March), page 13, columns 2–4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 30 March), page 13, column 4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 6 April), page 4, columns 3–4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 6 April), page 13, column 1.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 6 April), page 13, columns 2–3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 6 April), page 13, columns 3–4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 6 April), page 13, column 4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 4, column 4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 13, column 1.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 13, columns 1–2. Signed “Outsider.”

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 13, columns 2–3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 13, column 3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 13 April), page 13, columns 3–4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 20 April), page 13, column 1.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 20 A pr il), page 13, columns 1–2.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 20 April), page 13, columns 2–3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 20 April), page 13, column 3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 20 April), page 13, column 3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 27 April), page 4, column 5.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 27 April), page 13, column 1.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 27 April), page 13, columns 1–3.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 27 April), page 13, columns 3–4.

The New-York Times, vol. 39 (Sunday, 27 April), page 13, columns 4–6.

El Progreso Matemático, vol. 1 (20 December), 297–300.

The Nation, vol. 52 (12 February) 139, filmed at P 00043, page 99.

The Nation, vol. 52 (19 February) 160, filmed at P 00043, pages 100–101. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 52 (12 March) 217–218, filmed at P 00043, pages 101–103. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 52 (12 March) 217–218, filmed at P 00043, pages 101–103. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 52 (12 March) 217–218, filmed at P 00043, pages 101–103. Reply to letters. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 53 (9 July) 32–33, filmed at P 00043, pages 107–110.

The Nation, vol. 53 (8 October) 283, filmed at P 00043, pages 112–113.

The Nation, vol. 53 (15 October) 302, filmed at P 00043, page 114.

The Nation, 53 (22 October) 313–314, filmed at P 00043, pages 114–115. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 53 (22 October) 313–314, filmed at P 00043, pages 114–115, Reply to letter.

The Nation, vol. 53 (12 November) 372, filmed at P 00043, pages 115–117. Signed letter.

The Nation, vol. 53 (12 November) 375, filmed at P 00043, page 117.

The Nation, vol. 53 (19 November) 389–390, filmed at P 00043, pages 118–120. Letter.

The Nation, 53 (26 November) 408, filmed at P 00043, pages 120–122. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 53 (26 November) 415, filmed at P 00043, pages 123–124.

The Nation, 53 (3 December) 426, filmed at P 00043, pages 124–127. Letter.

The Nation, vol. 53 (17 December) 474, filmed at P 00043, pages 127–128.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, New York City, 10–12 April. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1891, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 170, 52d Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1892, p. 16. R 1028 may be relevant to this paper.

Read before the National Academy of Sciences, New York City, 10–12 April, and “discussed by Mr. Peirce.” Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1891, Senate Mis. Doc. No. 170, 52d Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 16; see P 00461.

New-York Daily Tribune, (Friday, 2 January), page 5, column 5.

New-York Daily Tribune, (Tuesday, 6 January), page 14, column 5. This is a response to several articles which were critical of Peirce’s account of the phrase in the Century Dictionary. Those earlier articles are in the same newspaper at: Friday 19 December 1890, page 10, column 2; Tuesday 23 December 1890, page 16, columns 5-6; Friday 2 January 1891, page 5, column 5. Fisch, First Supplement.

Report of the Superintendent of the U.S. Coast and Geodetic Survey, 7890, House Ex. Doc. No. 80, 51st Congress, 2d Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 104.

El Progreso Matemático, vol. 2, 170–173.

Mind, new series 1, 126–132.

The Monist, vol. 2 (July), 560–582.

The Monist, vol. 2 (July), 618–623.

The Monist, vol. 3 (October), 68–96.

The Nation, vol. 54 (3 March) 169, see 0 00488. Reply to a letter. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 54 (2 June) 417.

The Nation, vol. 54 (23 June) 472–473.

The Nation, vol. 55 (14 July) 35.

The Nation, vol. 55 (11 August) 114–115.

The Nation, vol. 55 (27 October) 324–325.

The Nation, vol. 55 (10 November) 359–360.

The Open Court, vol. 6 (1 September), 3374.

The Open Court, vol. 6 (22 September), 3391–3394.

The Open Court, vol. 6 (13 October), 3415–3418.

Science, vol. 19 (8 January), 17–18.

Sun and Shade, vol. 4 (August), photogravure numbered XC, with short biographical sketch.

“Namenregister zum 1–15 Bande (1877–1891).” von Fr. Strobel, Beiblätter zu den Annalen der Physik und Chemie. Peirce’s name is given at p. 132 with references to mentions of his work in the Beiblätter. Additional bibliographic references to Peirce’s articles are to be found in the following volumes of the Beiblätter: 6 (1882), 830; 7 (1883), 80.

Part one of a review of Napoléon lntime, by Arthur Lévy, The Independent, vol. 45 (21 December), 1725–1726.

Part two of a review of Napoléon lntime, by Arthur Lévy, The Independent, vol. 45 (28 December), p. 1760.

By Dr. Ernst Mach, The Monist, vol. 4 (October), 152–153, at p. 153.

The Nation, vol. 56 (2 February) 90.

The Nation, vol. 57 (27 July) 65.

The Nation, vol. 57 (3 August) 88–89.

The Nation, vol. 57 (24 August) 143.

The Nation, vol. 57 (5 October) 248. Reply to a letter; see O 00534.

The Nation, vol. 57 (19 October) 293–294.

The Nation, vol. 57 (26 October) 313–314.

The Nation, vol. 57 (7 December) 431.

The Open Court, vol. 7 (27 July), 3750.

In The Science of Mechanics, by Ernst Mach, translated from the second German edition by Thomas J. McCormack, Chicago: The Open Court Publishing Co., 1893, p. 280–286.

Privately printed prospectus for an edition of Peregrinus. P. 16. An announcement of this prospectus appeared in The Nation, vol. 58 (11 January 1894) 30 (P 00558), which suggests that it had already been printed in 1893.

Privately printed brochure announcing Peirce’s proposed work in twelve volumes, planned for sale through subscription.

Paper read before the American Mathematical Society, 24 November. Cited in Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, vol. 1 (December), 77.

The Nation, vol. 58 (4 January) 19.

The Nation, vol. 58 (11 January) 31. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 58 (22 February) 139. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 58 (19 April) 299.

The Nation, vol. 58 (31 May) 415–416.

The Nation, vol. 59 (5 July) 17.

The Nation, vol. 59 (12 July) 34–35. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 59 (19 July) 52–53.

The Nation, vol. 59 (22 November) 383. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, 59 (29 November) 409.

The Nation, vol. 59 (6 December) 430–431.

Presented at the meeting of the New York Mathematical Society on 7 April. Cited in Bulletin of the New York Mathematical Society, vol. 3 (May 1894), 199–200.

The New-York Times (8 April), page 8, column 1. This article is a report on the 7 April 1894 meeting of the New York Mathematical Society at which Peirce exhibited an arithmetic by Rollandus (dated 1424). A translation (presumably by Peirce) of Rollandus’ dedicatory letter is given in this article.

The Evening Post, New York, vol. 94 (Monday, 28 January), page 7, columns 1–2. See R 1401.

The Evening Post, New York, vol. 94 (Monday, 4 February), page 7, column 2.

The Nation, vol. 60 (14 March) 208.

The Nation, vol. 60 (21 March) 226–227. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 60 (4 April) 265. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 60 (11 April) 284–285.

The Nation, vol. 60 (30 May) 431–432. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 61 (11 July) 34–35.

The Nation, vol. 61 (22 August) 139–140. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 61 (14 November) 353–354.

The Nation, vol. 61 (28 November) 395.

The Nation, vol. 61 (26 December) 464. Signed “S.” Probably by Peirce.

The American Historical Review, vol. 2 (October), 107–113.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 18 (April), 145–152.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution to July 1894, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 191–196.

New York: D. Appleton and Co. London: William Heinemann, 1897. We have filmed the edition of 1897, published in London by William Heinemann. See drafts in R 1517.

Lecture before the Mathematical Department, Bryn Mawr College. Cited in Annual Report of the President of Bryn Mawr College, 1896–1897, Philadelphia: Alfred J. Ferris, Printer, 1898, p. 35. R 25 is probably for this lecture.

The Monist, vol. 6 (January), 312.

The Nation, vol. 62 (9 January) 42. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 62 (6 February) 122. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 62 (13 February) 147.

The Nation, vol. 62 (26 March) 261–262.

The Nation, vol. 62 (23 April) 330–331.

The Nation, vol. 62 (21 May) 404.

The Nation, vol. 63 (3 September) 181–182.

American Journal of Mathematics, vol. 19, 381–382.

The Evening Post, New York City, vol. 96 (Tuesday, 16 March), page 7, columns 3–4.

The Monist, vol. 7 (January), 161–217.

The Monist, vol. 7 (April), 453–458.

The Nation, vol. 65 (4 November) 362–363.

The Nation, vol. 65 (25 November) 424.

The Nation, vol. 65 (30 December) 524–525.

The American Historical Review, vol. 3 (April), 526–528.

1. February 10, Philosophy and the Conduct of Life; 2. February 14, Types of Reasoning; 3. February 17, The Logic of Relatives; 4. February 21, The First Rule of Logic; 5. February 24, Training in Reasoning; 6. February 28, Causation and Force; 7. March 3, Habit; 8. March 7, The Logic of Continuity. Titles cited in a pamphlet announcing the lecture series. Manuscripts for these lectures survive as follows: 1, R 437; 2, R 441; 3, R 438 or 440 (?); 4, R 442; 5, MSS 444 and 445; 6, R 443 and R 446; 7, R 951; 8, R 948–R 950; also R 435, R 439, R 440, R 940, and R 941.

Educational Review, vol. 15 (March), 209–216. The article ends with the phrase, “To be continued.” but no continuation has been found.

Boston: Lamson, Wolff and Company, references to Peirce’s Lowell Lectures at p. 63 and 88; see also p. 31.

The Monist, vol. 9, 44–62.

The Nation, vol. 66 (31 March) 250–251.

The Nation, vol. 66 (21 April) 311.

The Nation, vol. 66 (28 April) 330–331. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 67 (14 July) 38–39. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 67 (22 September) 228–229.

The Nation, vol. 67 (20 October) 300–301.

The Nation, vol. 67 (24 November) 390.

The Evening Post, New York City, vol. 98 (Wednesday, 16 August), page 5, columns 4–6. Reprinted in Progressive Age (see P 00705).

The Nation, vol. 68 (2 February) 95–96.

The Nation, voI. 68 (16 March) 210.

The Nation, vol. 68 (27 April) 316–317.

The Nation, vol. 68 (18 May) 376. Peirce’s editorial reply to a letter by Cajori. Filmed at O 00687.

The Nation, vol. 68 (25 May) 403.

The Nation, vol. 68 (25 May) 405.

The Nation, vol. 68 (22 June) 482–483.

The Nation, vol. 69 (6 July) 18. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 69 (27 July) 77–78.

The Nation, vol. 69 (24 August) 154. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 69 (7 September) 192–193.

The Nation, vol. 69 (21 September) 231.

The Nation, vol. 69 (28 September) 248–249. Probably by Peirce.

The Nation, vol. 69 (19 October) 303–304.

The Nation, vol. 69 (14 December) 455.

Paper read before the National Academy of Sciences, New York City, 14–15 November. Cited in Report of the National Academy of Sciences for the Year 1899, Senate Document No. 117, 56th Congress, 1st Session, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1900, p. 13. R 153–R 158 may be related to this presentation.

The Bookman, vol. 11 (July), 491–492.

The Nation, vol. 70 (4 January) 18.

The Nation, vol. 70 (25 January) 78.

The Nation, vol. 70 (1 February) 97–98.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 February) 128.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 February) 128, filmed at P 00720.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 February) 128, filmed at P 00720.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 February) 128, filmed at P 00720.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 March) 203–204.

The Nation, vol. 70 (15 March) 204, filmed at P 00725.

The Nation, vol. 70 (22 March) 230.

The Nation, vol. 70 (10 May) 366.

The Nation, voI. 70 (17 May) 384–385.

The Nation, vol. 70 (31 May) 417.

The Nation, vol. 70 (28 June) 504–505.

The Nation, vol. 71 (19 July) 59.

The Nation, vol. 71 (26 July) 78–79.

The Nation, vol. 71 (26 July) 79, filmed at P 00738.

The Nation, vol. 71 (30 August) 178.

The Nation, vol. 71 (20 September) 235–236.

The Nation, vol. 71 (18 October) 314–315.

The Nation, vol. 71 (22 November) 410–411.

The Nation, vol. 71 (6 December) 449–450.

The Nation, vol. 71 (27 December) 515–516.

Science, new series 11 (16 March), 430–433. Dated by Peirce as “Milford, Pa., Feb. 18, 1900.”

Science, new series 11 (20 April), 620–622.

The American Historical Review, vol. 6 (April), 557–561.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 7899, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 367–373.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1899, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 549–561.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 187–193.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 461–478.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 493–506.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 527–533.

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 551–564.

Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1900, Washington: Government Printing Office, p. 693–699.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 309. Introductory matter (p. ii-xxiv) for this dictionary is filmed here.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 318, see also 318–321.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 338.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 411.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 414.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 518–519.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 525–526.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 529.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 530.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 531–532.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 537–538.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 542–543.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 554.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 561.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 574.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 600–601.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 603.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 1, 641–643, 644. Part of this article is by C. Ladd-Franklin (643–644).

The Evening Post, New York City, vol. 100 (Saturday, 12 January), section three, page 1, columns 1–3.

The Nation, vol. 72 (24 January) 76.

The Nation, vol. 72 (28 March) 258–259.

The Nation, vol. 72 (13 June) 479–480.

The Nation, vol. 72 (20 June) 497–498.

The Nation, vol. 73 (1 August) 99–100.

The Nation, vol. 73 (15 August) 139–140.

The Nation, vol. 73 (24 October) 325–326.

The Popular Science Monthly, vol. 58 (January), 296–306.

Verhandlungen der vom 25 September bis 6 October 1900 in Paris abgehaltenen Dreizehnten Allgemeinen Conferenz der lnternationalen Erdmessung, II Theil: Spezialberichte and wissenschaftliche Mittheilungen, Berlin: Verlag von Georg Reimer, Appendix B, I (p. 330–335).

In Annual Report of the Board of Regents of the Smithsonian Institution for the Year Ending June 30, 1901, Washington: Government Printing Office, pp. 317–340.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 1. Introductory matter for vol. 2 (p. iii-xvi) is filmed here.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 1–2, filmed at P 00806.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 3.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 6.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 6–7, filmed at P 00809.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 20–23.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 23–27, filmed at P 00811.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 27–28, filmed at P 00811.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 28, filmed at P 00811.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 30.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 37.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 43.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 44.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 44–45, filmed at P 00818.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 47.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 50–55.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 55, filmed at P 00821.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 75.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 77.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 87.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 87–89, filmed at P 00825. The first few sentences of this article are by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 89–93, filmed at P 00825.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 94, filmed at P 00825.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 94, filmed at P 00825.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 98–99. Only part of this article is by Peirce.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 117– 118.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 143.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 145–146 filmed at P 00833. Parts of this article are by other authors.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2;

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 148, filmed at P 00833. Another author continues the article.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 179.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 180.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 180, filmed at P 00838.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 181, filmed at P 00838.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 181, filmed at P 00838.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 182. Part of the article is by another author.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 183, filmed at P 00842.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 190.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 198.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 199, filmed at P 00845.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 206. Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 219.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 253.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 258.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 259, filmed at P 00850. Burks, Bibliograohy.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 263.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 264.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 265, filmed at P 00853.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 265–266, filmed at P 00853.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 266, filmed at P 00853.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 266, filmed at P 00853.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 276.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 281–282. The first two paragraphs are by John Dewey.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 286–287.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 287, filmed at P 00860.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 287–288, filmed at P 00860.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 290.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 306–307. The last paragraph is by other authors.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 309. Part of this article is by J. Jastrow.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 310.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 311–312, filmed at P 00866. Part of this article is by John Dewey.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 313–315, filmed at P 00866. Part of the article ending with p. 314, col. 1, is by John Dewey.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 315, filmed at P 00866.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 315–316, filmed at P 00866.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 321–323. Parts of this article are by other authors.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 323, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 323–324, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 324–325, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 325, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 325, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 325–326, filmed at P 00871. Part of this article is by another author.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 326–329, filmed at P 00871. Parts of this article are by other authors.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 329, filmed at P 00871.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 330–331.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 337. Part of this article is by another author.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 338.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 341.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 341, filmed at P 00883.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 341, filmed at P 00883.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 342–343.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 343, filmed at P 00886.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 353–355.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 355, filmed at P 00888.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 355–356, filmed at P 00888.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 358. Part of this article is by J. Jastrow.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 359, filmed at P 00891. Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 361–370. Only part of this article is by Peirce and Baldwin (361–362) ; the remainder is by other authors.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 370, filmed at P 00893.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 371, filmed at P 00893.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 373.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 373–374, filmed at P 00896.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 401–402. Part of this article is by J. Dewey.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 408–409.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 410–412.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 415. Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 415, filmed at P 00901.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 415, filmed at P 00901. Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 426–428. Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 434.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 434–435, filmed at P 00905. Part of this article is by J. Royce.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 438–439.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 447–450.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 463 Part of this article is by J. M. Baldwin.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 464.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 464–465, filmed at P 00910.

Dictionary of Philosophy and Psychology, ed. J. M. Baldwin, New York: Macmillan, vol. 2, 466.